Conserving Scrapbooks: A Unique Conservation Challenge

August 1st, 2016I have spent this summer as the second Ringle Summer Intern in the Stannard Conservation Lab at the University of Kansas. My internship focused on a collection of 41 scrapbooks held by the University Archives. The project involved developing a survey tool, surveying the collection, identifying items for treatment, treating some items, and rehousing/housing modification all of the scrapbooks. Most of the books dated from the early 1900’s. They showcase student life leading up to and in the early stages of World War One. This insight into student life at a very interesting and volatile time, especially as we come to the 100 year anniversary of the United States entering the war, is why the Archives uses these materials as teaching tools with undergraduate students. The scrapbooks also include very interesting objects, like firecrackers with the line written next to them, “We shot up the house.” I was unable to discover which house they were talking about but I have no doubt they would have been in serious trouble for doing that today! From a conservation perspective these firecrackers required some consolidation and I discovered one of the fuses is still in place!

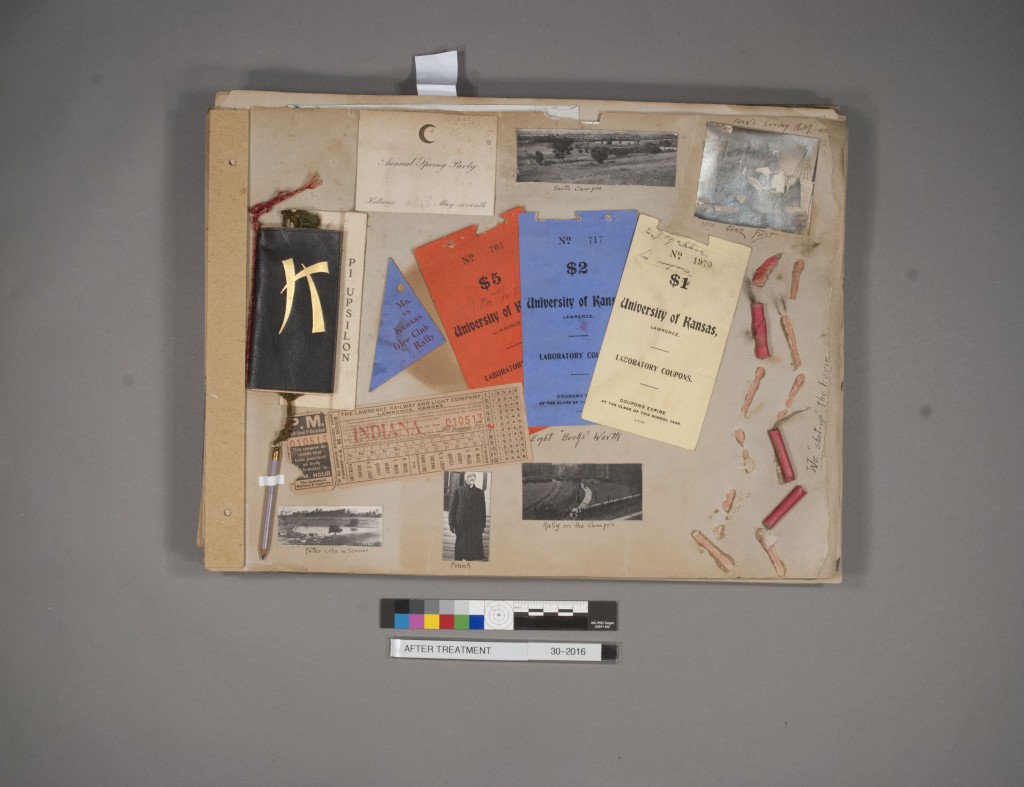

Firecrackers in a scrapbook compiled by Emery McIntire, after treatment.

Call Number: SB 71/99 McIntire. Click image to enlarge.

For more information about the project please see the story published in the Lawrence Journal-World in July: http://www2.ljworld.com/news/2016/jul/04/century-old-ku-student-scrapbooks-pose-preservatio/.

And for some video footage of the treatments please see the coverage from 41 Action News: http://www.kshb.com/news/region-kansas/ku-working-to-preserve-former-students-scrapbooks.

I came into the project most excited about the problem-solving aspects of working with scrapbooks and I was not disappointed. Many conservators greatly enjoy the problem-solving we get to do every day to determine the correct treatment for objects. For conservation purposes scrapbooks are exceedingly complex and complicated objects. Usually they are made of cheap materials and contain a variety of attachment methods. This means that once they make it to a conservator’s bench they are normally quite fragile. The binding may be failing, the support paper is usually brittle, and the various types of attachment—glue, tape, staples, pins—may have partially or completely failed. Given all of this, determining the most appropriate treatment is not always an easy task.

For the scrapbooks I treated I came across two main problems: What is the most efficient way to mend the innumerable tears to the support pages? What is the best way to conserve objects found in the scrapbooks? Some of these objects include firecrackers, a Red Cross bandage, and a 100 year old piece of hardtack.

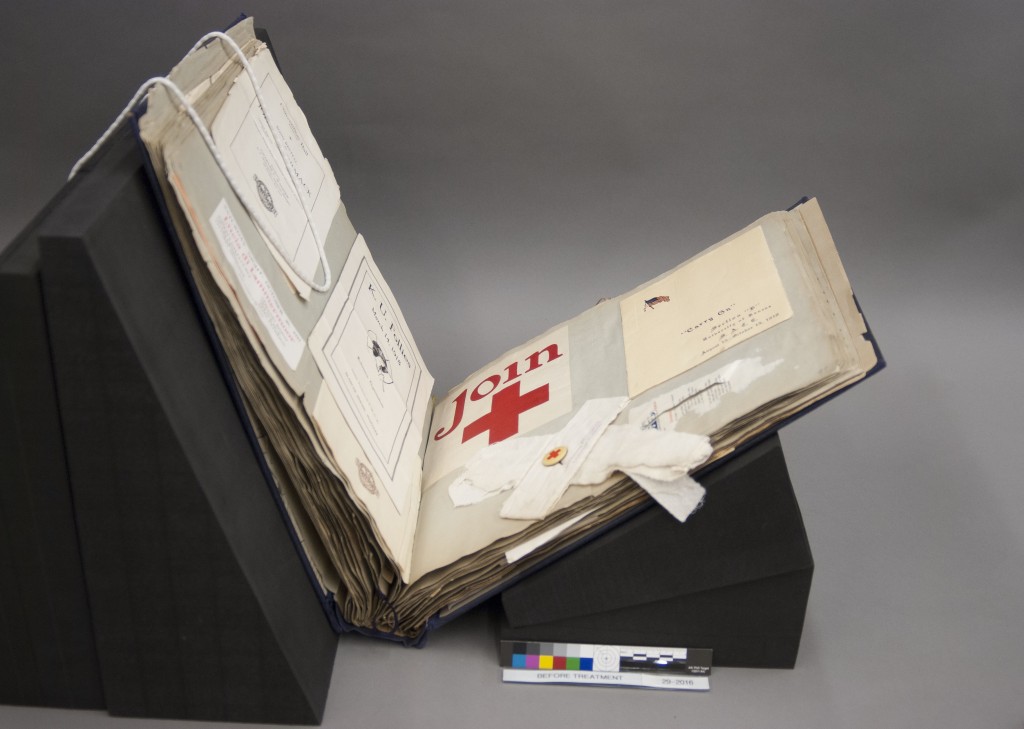

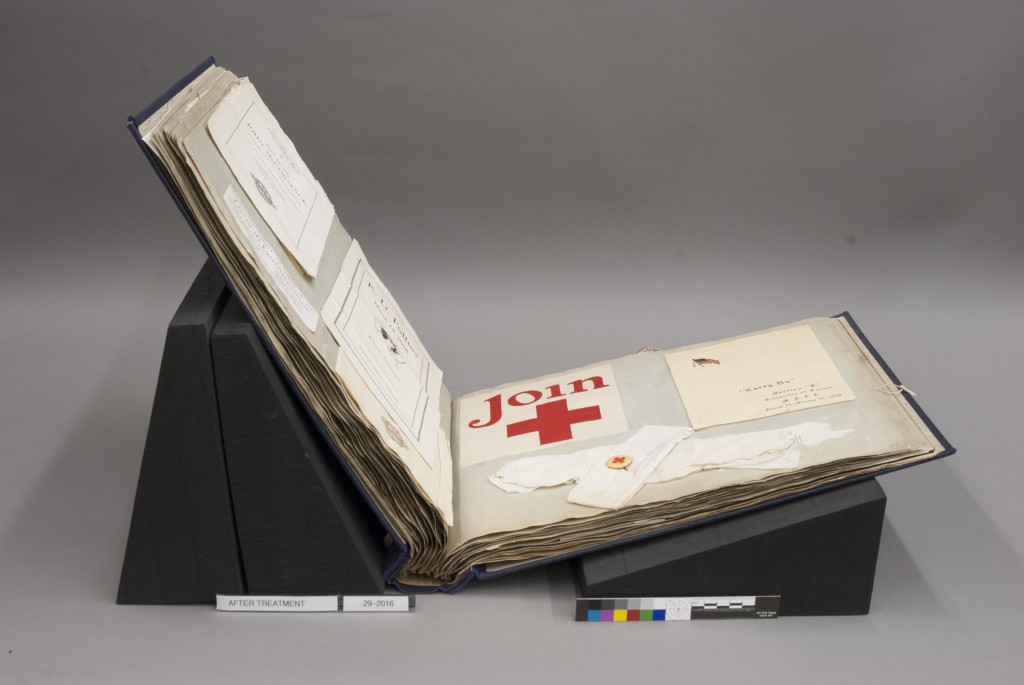

Red Cross bandage in a scrapbook compiled by Florence Harkrader,

before (top) and after (bottom) treatment. Call Number: SB 71/99 Harkrader.

Click images to enlarge.

I found that the most efficient way to repair all the tears—averaging around 10 tears per page—was to use a remoistenable repair paper. I made this using a 10gsm tengujo Japanese paper and a 50/50 mix of wheat starch paste and methyl cellulose. Once this was dry I was able to score it into many different sized strips to fit the various sized tears I was repairing.

Of the two objects mentioned the bandage was the easier to conserve. It is pinned to the support page and can swivel a bit on the pin allowing it to extend beyond the edge of the book. This means that there are some creases and frayed areas that have developed over time. To conserve it I repositioned it to sit inside the edges of the book and flattened out the creases.

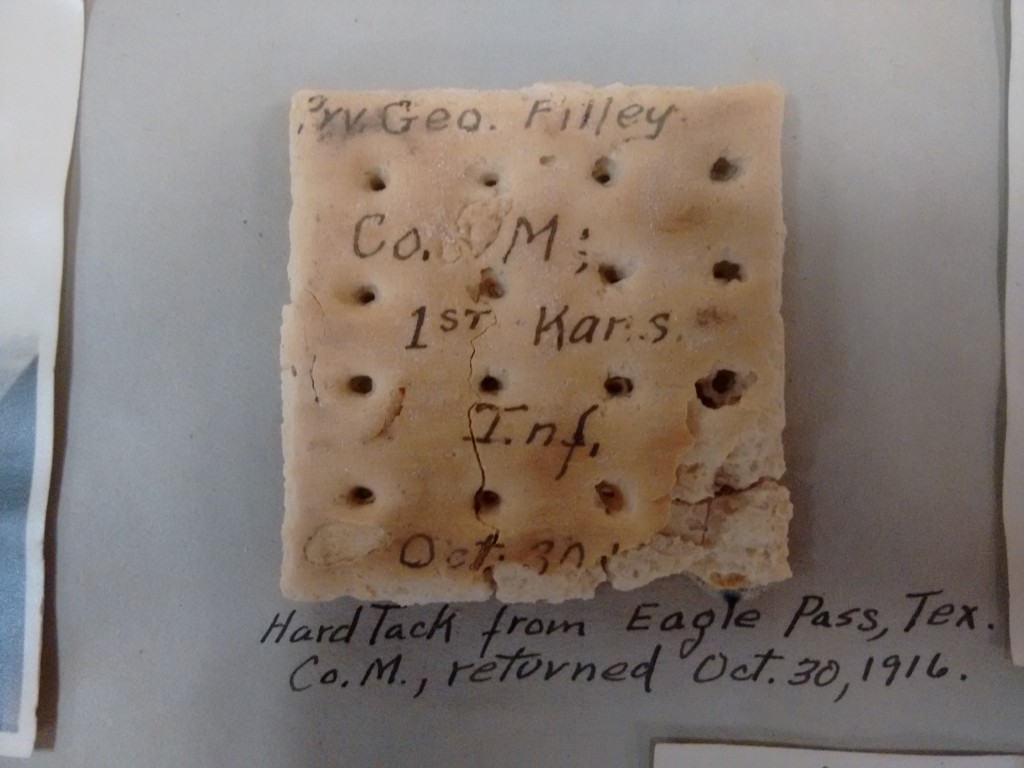

The hardtack required creative problem-solving. It had a number of problems. It was coming unstuck from the support paper, had a number of cracks, and has writing on it. The ink means that any organic solvent-based consolidant could not be used. Additionally, it was desirable to keep the hardtack on the page, rather than removing it and storing it separately. In the end it was decided to remove the page from the scrapbook (the book was already disbound and is not being rebound) and to store it in its own enclosure within the same box as the scrapbook. The hardtack was re-secured to the page using a very dry wheat starch paste. The page was put in a float mount and support pieces were made with cutouts for the hardtack on one side and a dance book on the other. All of this was then sandwiched between pieces of corrugated board with ties attached. This created a housing that will both protect the page and aid in flipping the page from one side to the other.

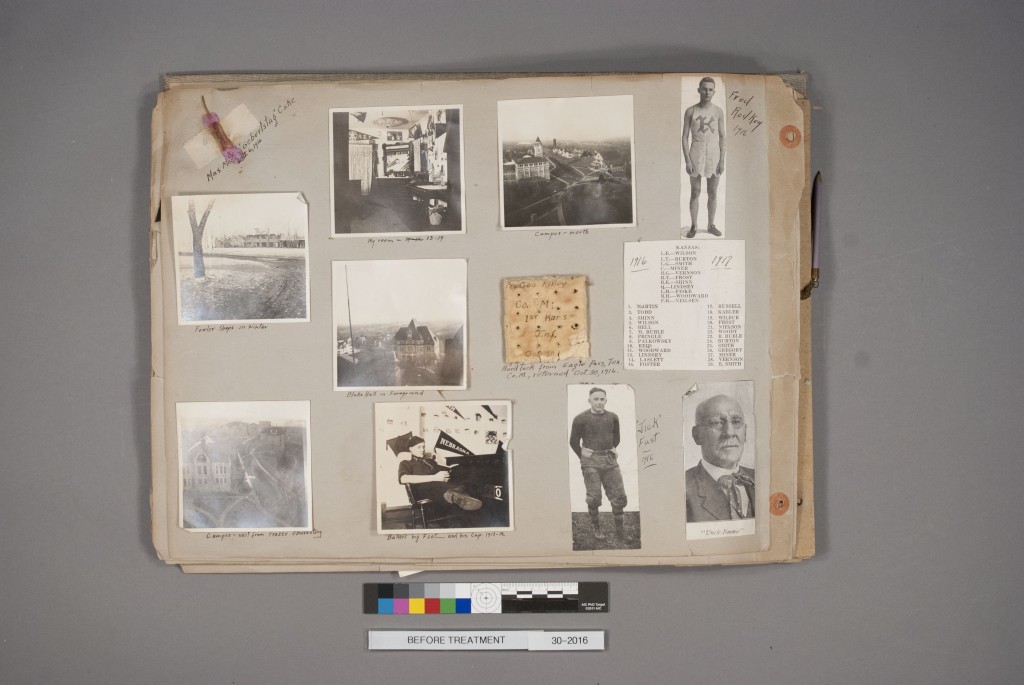

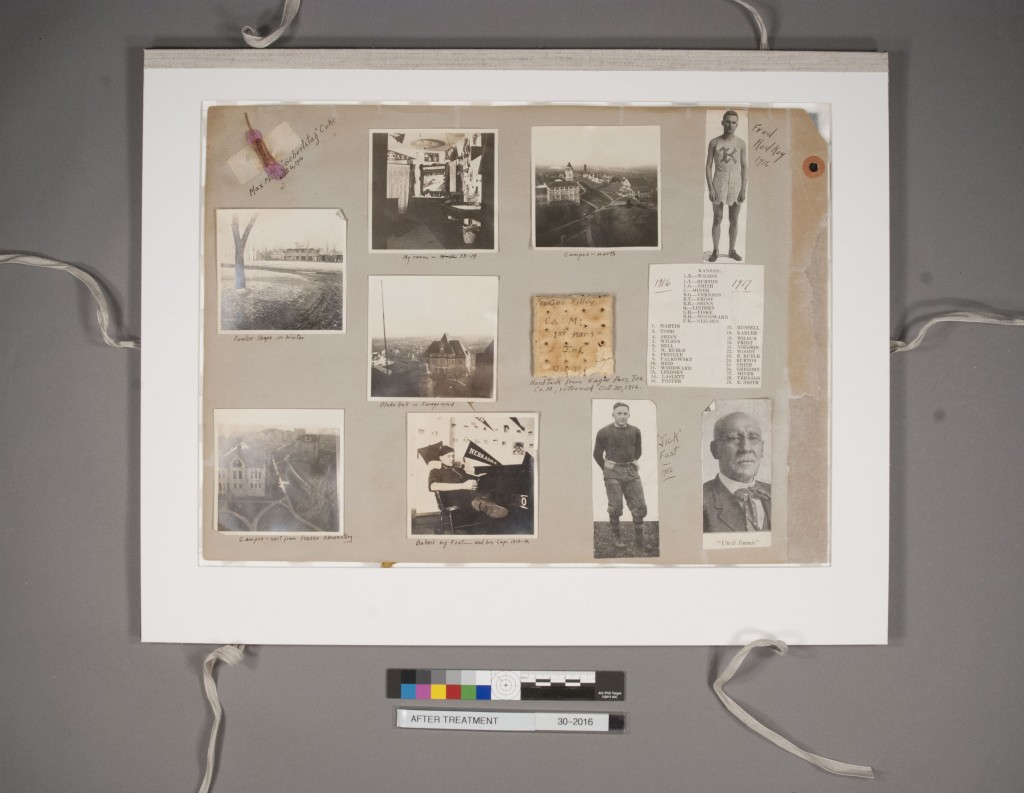

Page from Emery McIntire’s scrapbook, featuring a piece of hardtack,

before (top) and after (bottom) treatment. Call Number: SB 71/99 McIntire.

Click images to enlarge.

Detail of the hardtack. Call Number: SB 71/99 McIntire. Click image to enlarge.

This project allowed me to hone my skills in many areas of conservation. My project will allow for these scrapbooks to be accessed and stored more safely going forward. I highly recommend stopping by Spencer Research Library, calling one or two to the reading room, and losing yourself in KU’s past!

Noah Smutz

2016 Ringle Conservation Intern