The Mystery of MS A7

May 22nd, 2018This blog post has been a long time coming. I actually started writing about MS A7 last fall. I wanted to do a simple post that talked about this manuscript and highlighted its interesting watercolor and ink drawings. However, in the preliminary stages of my research, the information I found brought up a series of questions that I have been attempting to answer for the past few months. Here is a peek at what I have learned so far!

Prediche sul nome di Gesu is a late 15th to early 16th-century Italian manuscript. The manuscript features a series of sermons on the name of Jesus by Saint Bernardinus of Siena (San Bernardino in Italian). The content of the manuscript is pretty straightforward; it is the images that prompted serious questions for me. There are several full-page drawings that feature a monk involved in a series of activities that are confusing at best (and completely macabre at worst).

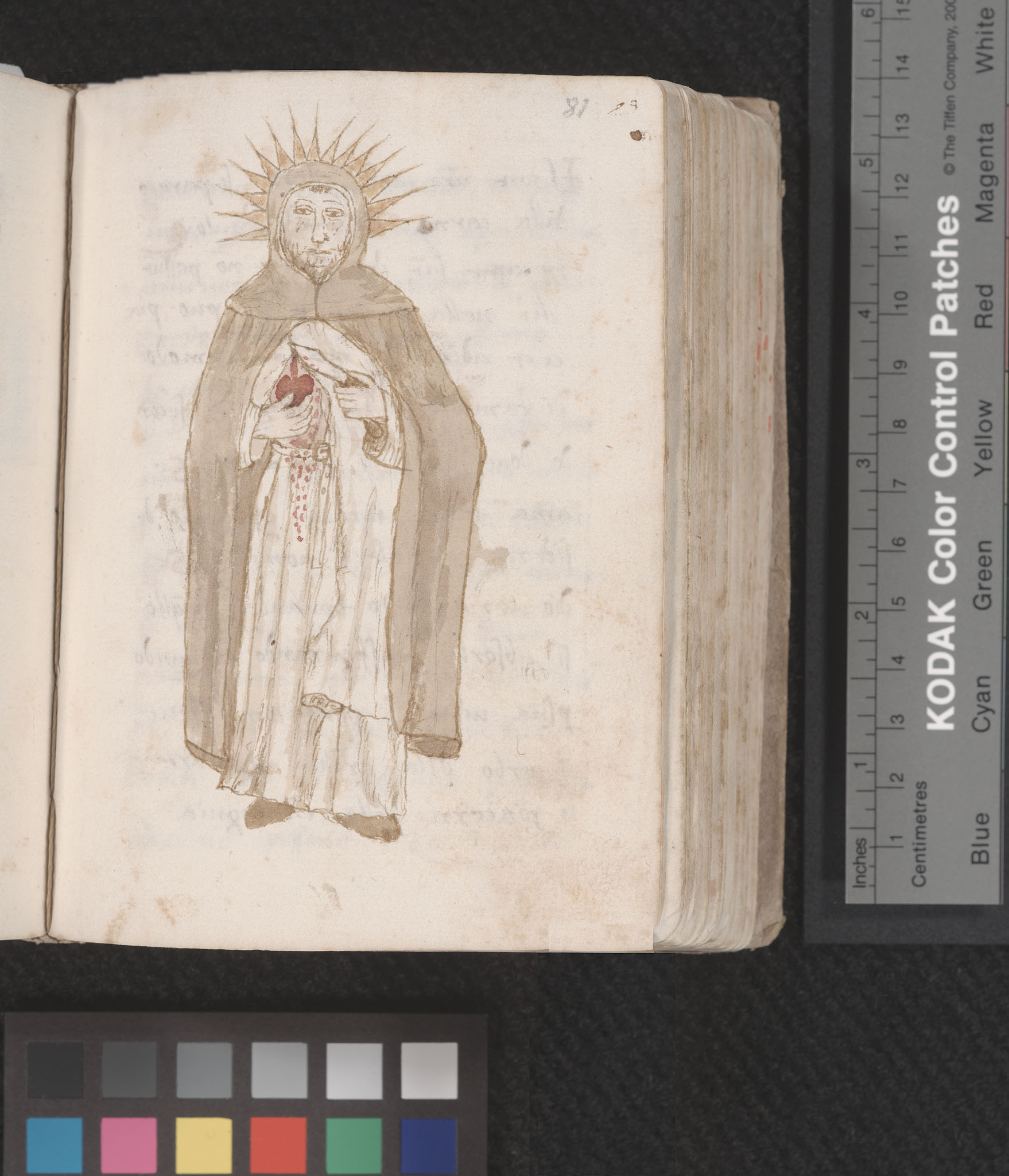

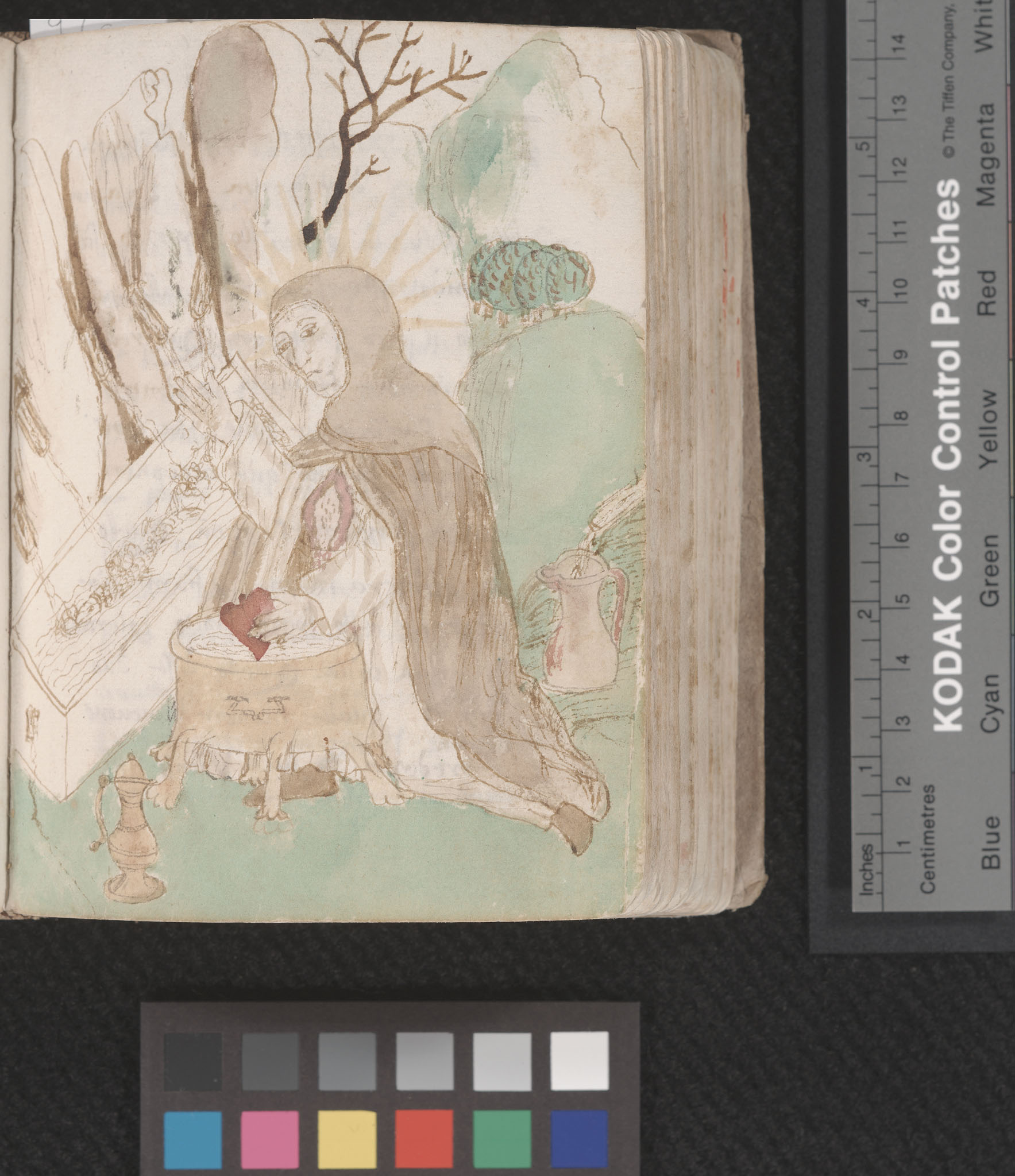

With the open chest wound and heart in hand, the image on the right was the one that initially piqued my interest

in this manuscript. How was the monk alive without his heart? Did the seeming improbability of what was happening

in the image mean this was the depiction of a vision or metaphor within the text? Folio 81r (left) and 88r (right)

from Saint Bernardinus of Siena’s Prediche sul nome di Gesu, Italy, circa late 15th-16th century.

Call Number: MS A7. Click images to enlarge.

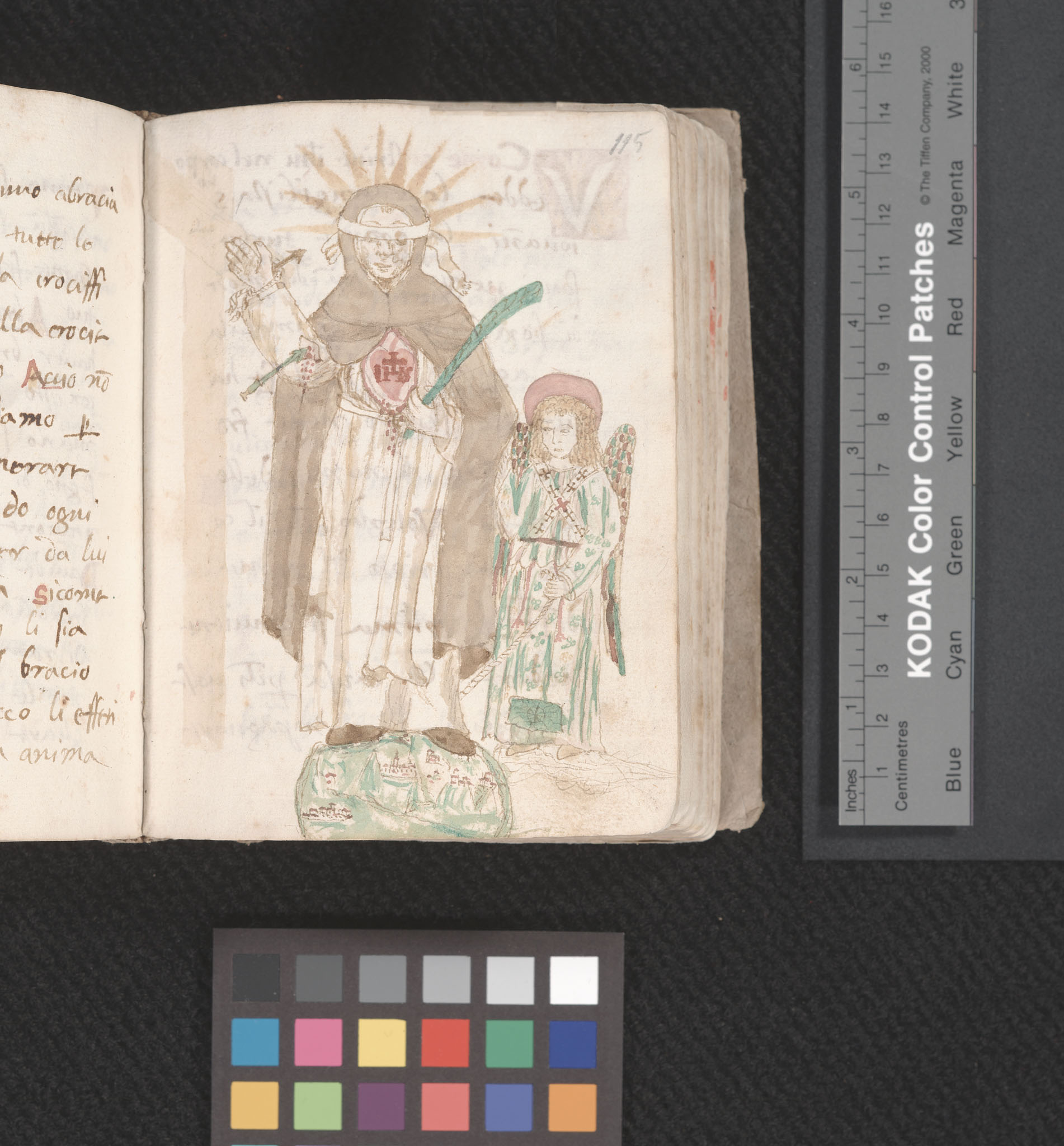

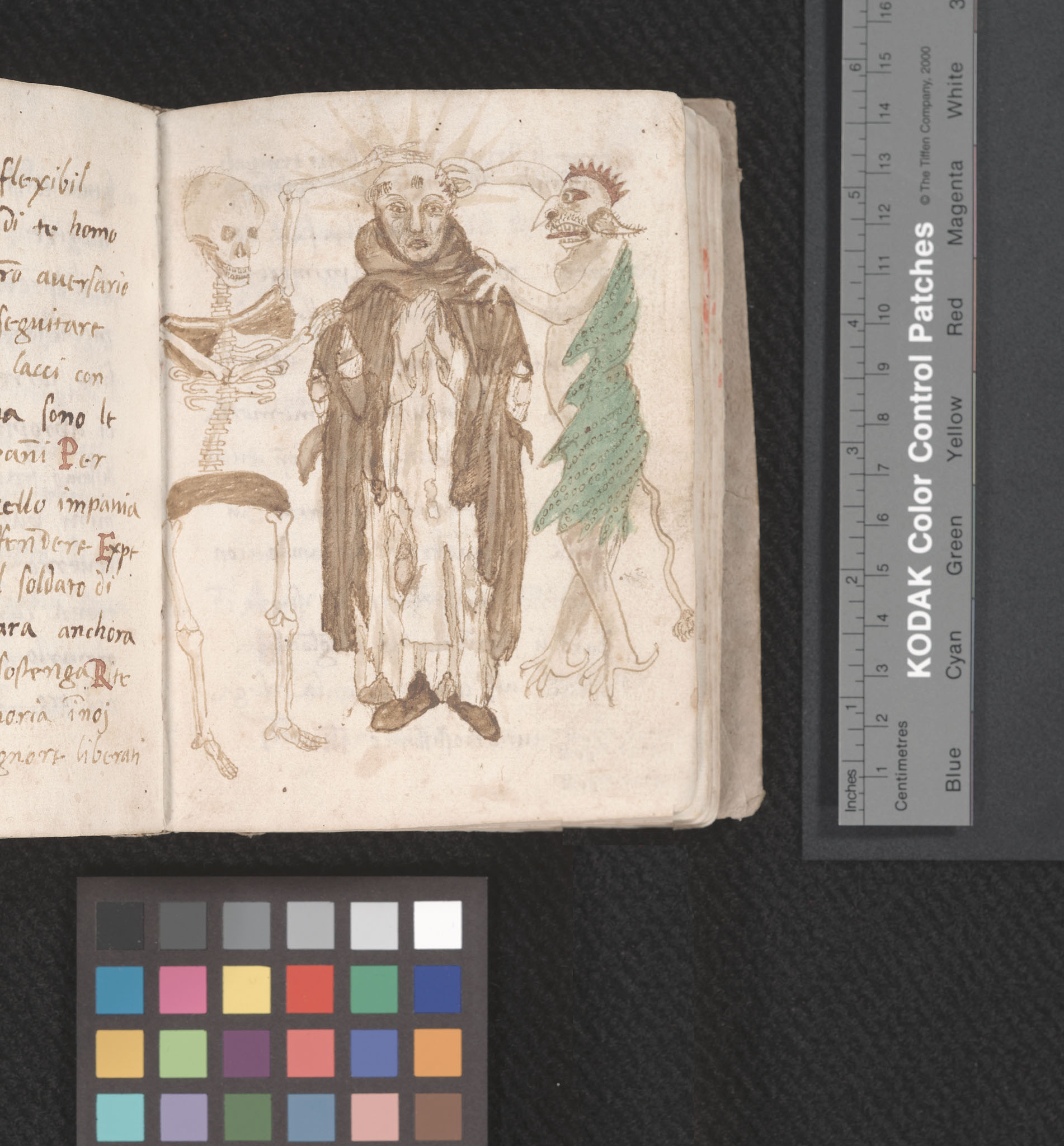

The image on the left has prompted so many questions. How does this image relate to the previous images of the monk?

Is it even supposed to be the same monk? Why is he blindfolded? Folio 115r (left) and 137r (right) from Saint Bernardinus

of Siena’s Prediche sul nome di Gesu, Italy, circa late 15th-16th century. Call Number: MS A7. Click images to enlarge.

Were these images meant to depict scenes from the life of San Bernardino? A series of visions the saint experienced? Preliminary research on the life of San Bernardino seemed to indicate that neither one of those conclusions was likely. I then turned to our records concerning the manuscript – accession files, catalogue entries, bookseller correspondence, etc. The lack of concrete information and answers in those records solidified my growing belief that little to no serious research had ever been done on this manuscript (not unusual with collections the size of ours). It became clear that if I wanted answers, I was going to have to find them myself. I had a hunch that the images were related to the text, possibly even very literal depictions of passages in the sermons. However, without any significant knowledge of Italian, I knew I needed quite a bit of help.

The next steps in my research process demonstrate just how lucky we are to have the amazing faculty we do at KU. First and foremost, our Special Collections curators, Karen Cook and Elspeth Healey, provided insight, access to files, suggestions of where to look next, and beginning translation help. The next step was to find someone to more fully translate the Italian and provide some more information about the images themselves. This led me to Dr. Areli Marina in the Kress Foundation Department of Art History here at KU.

Dr. Marina’s translation work and insight have helped me immensely. With her assistance, I have started to get a clearer picture of what is happening in the manuscript (my initial hunch seems to be on the right track). However, with each new bit of information, more questions continue to arise. For example, do these sermons and images have any connections to certain established monastic communities and their traditions? Hopefully, I will have more answers to share with you all soon!

Emily Beran

Public Services