No Taste for Innocent Pleasures: L. E. L. and the Nineteenth Century

November 15th, 2012Student Manuscripts Processor and Museum Studies Graduate Student Sarah Adams revises her ideas about the nineteenth century after working on the collection of British poet L. E. L.

When we think of English society in the nineteenth century, we often associate it with what we’ve read in classic novels. British literature and culture of that era seemed to me to lean heavily on polite social decorum and chaste modesty. With such stringent moral codes, people from these periods can at times appear dull compared to modern society. However, after working on a certain nineteenth-century collection in the processing department, I have a hard time believing this to be the case.

Two portraits of Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L. E. L.). Left: by S. Wright del; S. Freeman sc.; Right: by D. Maclise ; J. Thomson. Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L. E. L.) Collection. Call Numbers: MS 223 E1 (left) and MS 223 E2 (right). Click images to enlarge.

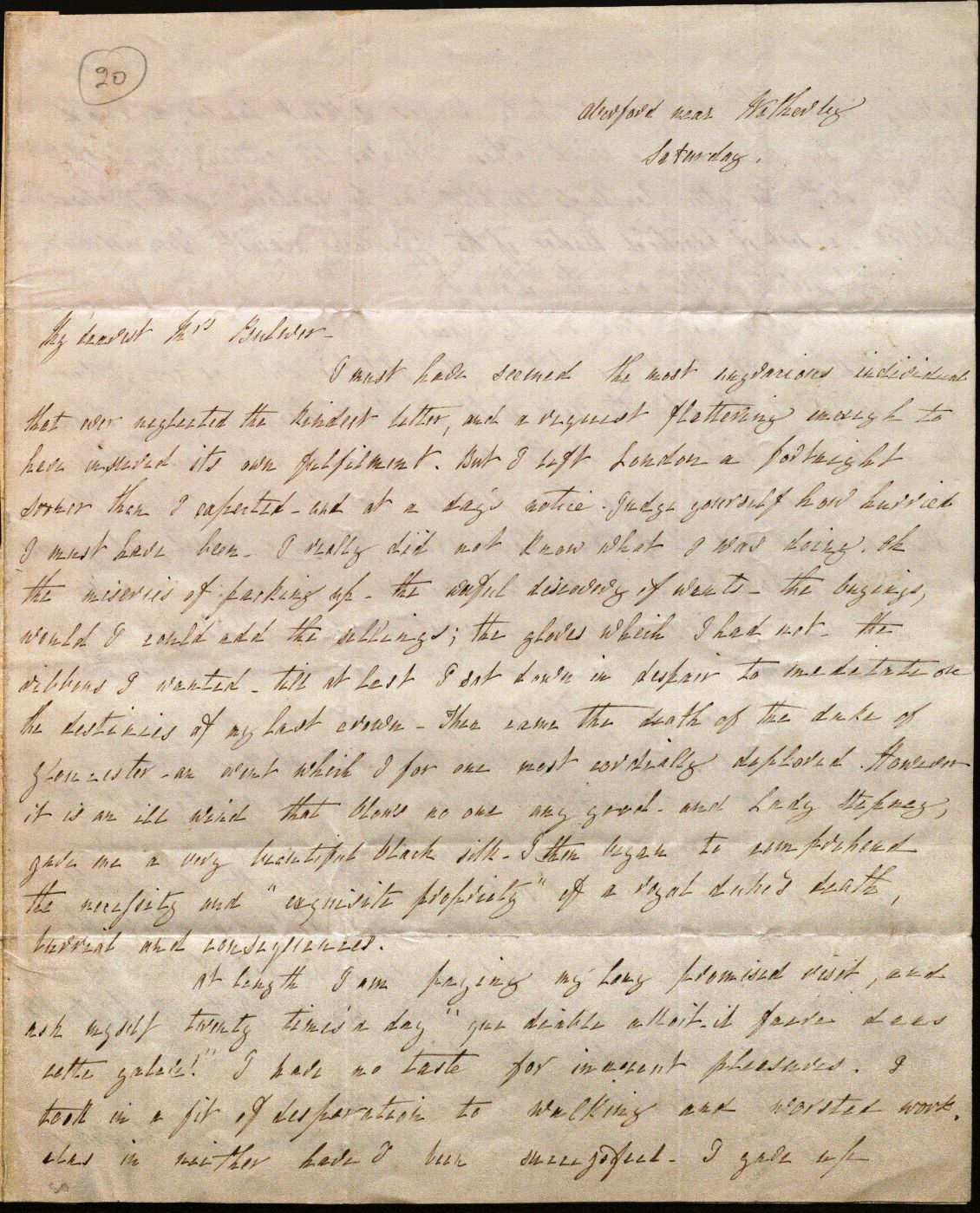

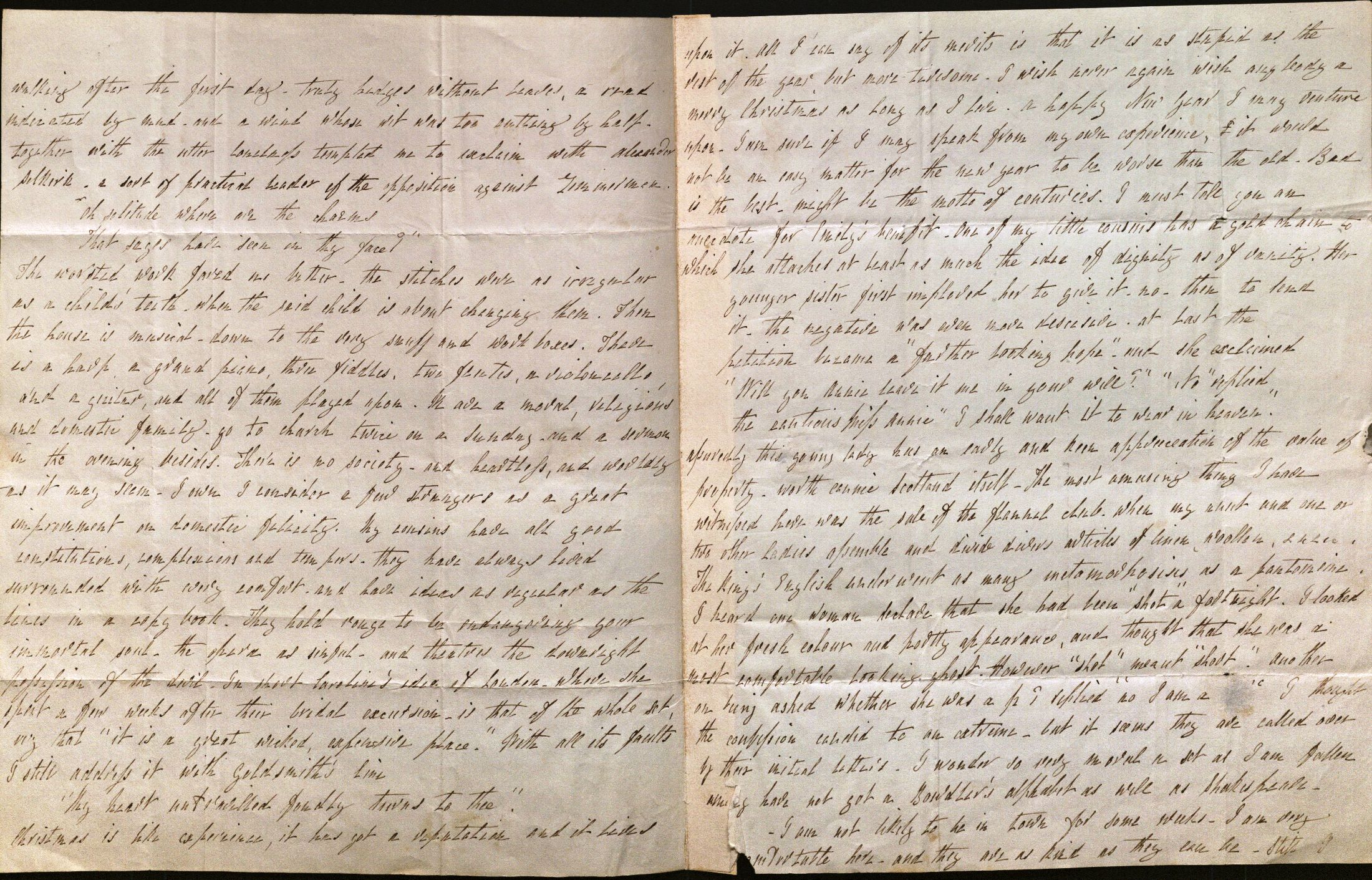

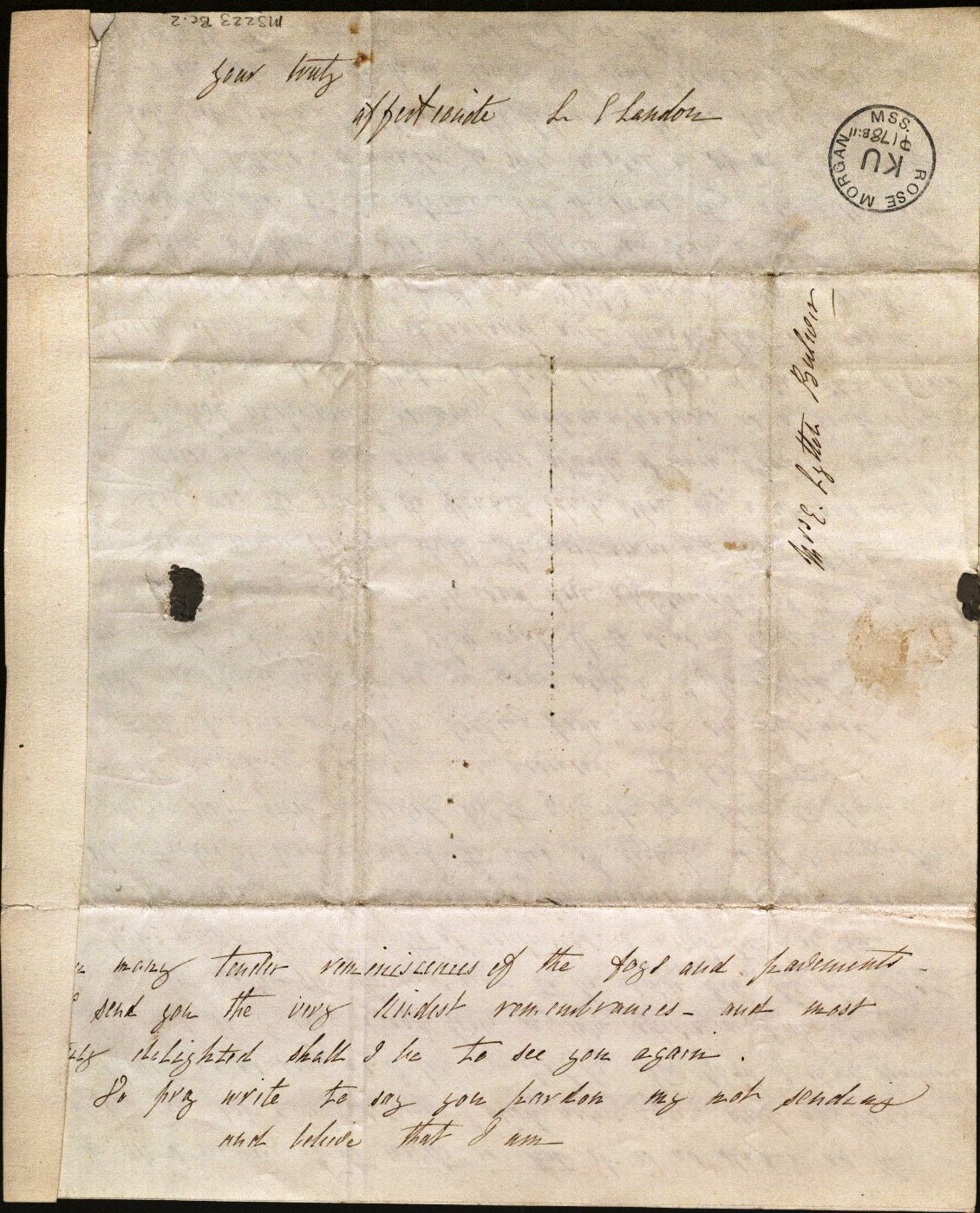

Letitia Elizabeth Landon (1802-1838), or L.E.L., was an English poet and novelist in the early nineteenth century. She was controversial in her time due to rumored inappropriate relations with a man, a broken engagement, and her suspicious death (perhaps by suicide). Her small collection at the Spencer Research Library (MS 223) includes some of her poetry as well as personal correspondence. In her letters, L.E.L. displays a certain frankness that I was surprised to see in that time period. She could be quite harsh on those she felt were unexciting or uninspired.

In one passage from a letter to Mrs. E. Lytton Bulwer [1834?], she said this of her cousin Caroline:

“My cousins have all good constitutions, complexions, and tempers. They have always lived surrounded with every comfort and have ideas as regular as the lines in a copy book. They hold rouge to be endangering your immortal soul, the opera as sinful, and theaters the downright profession of the devil. In short, Caroline’s idea of London, where she spent a few weeks after their bridal excursion, is that of the whole set, my that ‘it is a great, wicked, expensive place.’”

In another passage, she writes regarding her cousins’ ideas of recreation:

“I have no taste for innocent pleasures.”

Detail from the first page a letter from L. E. L. to Mrs. Bulwer. Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L. E. L.) Collection.

Call Number: MS 223 Bc2. Click image to enlarge

And further:

“One of my little cousins has a gold chain to which she attached at least as much the idea of dignity as of vanity. Her younger sister first implored her to give it – no – then to lend it. The negative nod even more decided. At last the petition became a ‘farther looking hope’ and she exclaimed, ‘Will you Annie leave it me in your will?’ ‘No,’ replied the cautious Miss Annie, ‘I shall want it to wear in Heaven.’”

This attitude toward her cousins likens L.E.L. to one of the many “villains” of Victorian literature. Perhaps, though, there was another side to nineteenth-century English society that some modern readers choose to ignore in the interest of romantic ideals we’ve grown to love in our favorite classics. I, for one, find it much more exciting to imagine this slightly wicked side in our beloved heroes and heroines.

Curious about L.E.L.’s work? Click here for a link to one of her poems, “Revenge.”

To read the entirety of the letter from L. E. L. to Mrs. E. Lytton Bulwer discussed in this post (MS 223: Bc.2), please click on the thumbnails below.

Sarah Adams

Student Manuscripts Processor and Museum Studies Graduate Student

Editor’s Note: An online finding aid for the Spencer Library’s Letitia Elizabeth Landon (L. E. L.) Collection will be available through our finding aids search portal in the coming weeks.