Manual Retouching of Glass Plate Negatives in the Hannah Scott Studio Collection: Ringle Conservation Internship

I began working as the Ringle Conservation Intern during the fall of 2024, drawn to the position as an art history graduate student with a budding interest in art conservation and passion for collecting antique photographs. Throughout the course of the semester, and the beginning of the spring 2025 semester, I was able to rehouse 2,400 glass plate negatives and contribute to the online database that will be used towards the creation of a future finding aid. Under the guidance of the incredibly kind and knowledgeable conservation staff, such as Whitney Baker, Charissa Pincock, and Kaitlin McGrath, I was able to take my first steps into the world of conservation and archival work, and will look back at this time fondly.

Throughout my time at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Conservation Lab, I was privileged with the ability of looking into the past through the eyes of Hannah Scott, the Independence, Kansas based photographer and studio owner who operated from the 1910’s into the 1940’s. Each glass plate negative that I carefully removed from their aged and yellowed envelopes showed me a moment frozen in time; a bride on her wedding day with her bouquet cascading to the floor, a baby with a wide, toothless, grin clutching a doll, or an elderly couple still donning the out-of-fashion garb of decades past. I became an undetected observer from a distant time, one who was able to watch children and families grow over the years as they returned time and time again to Hannah’s studio.

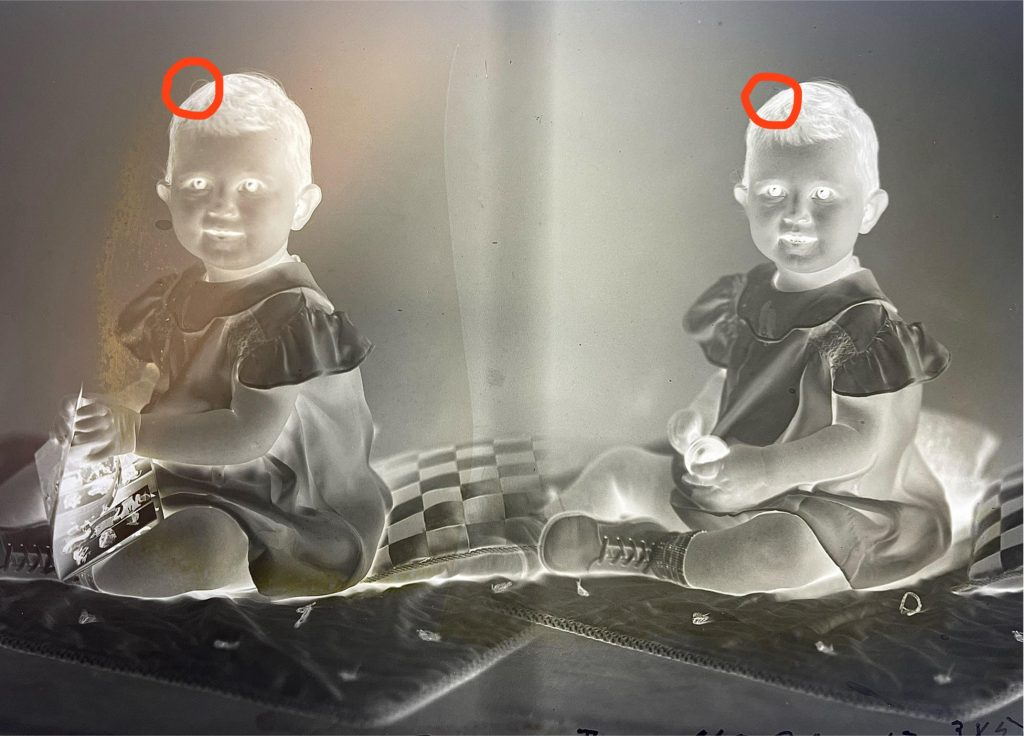

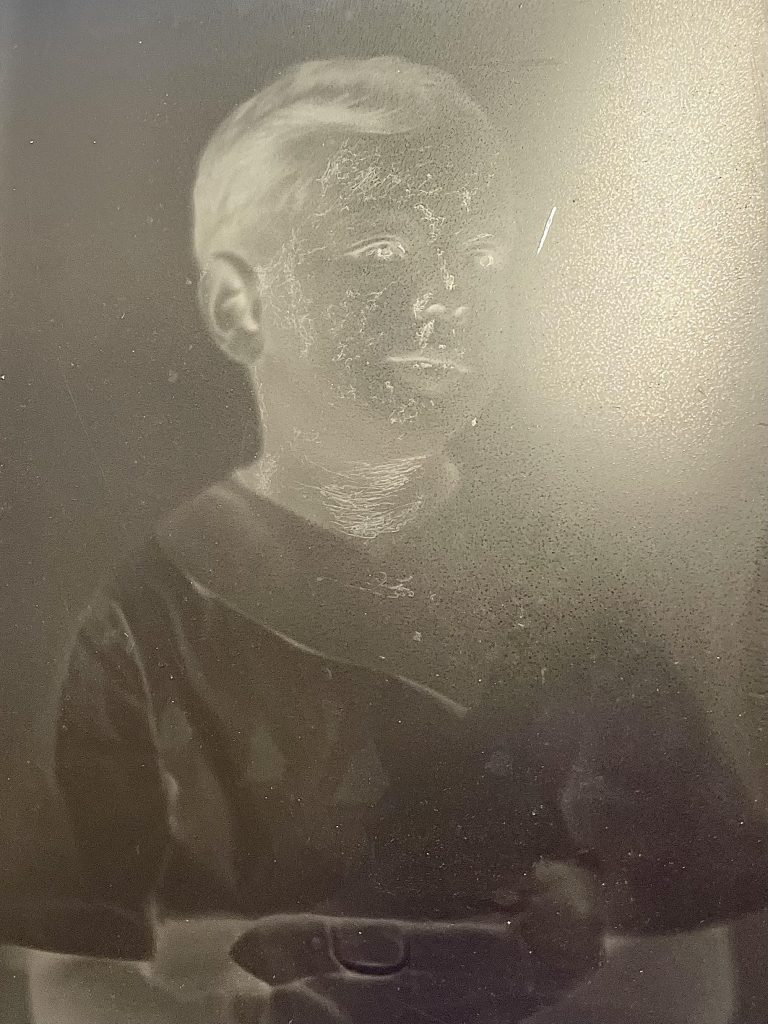

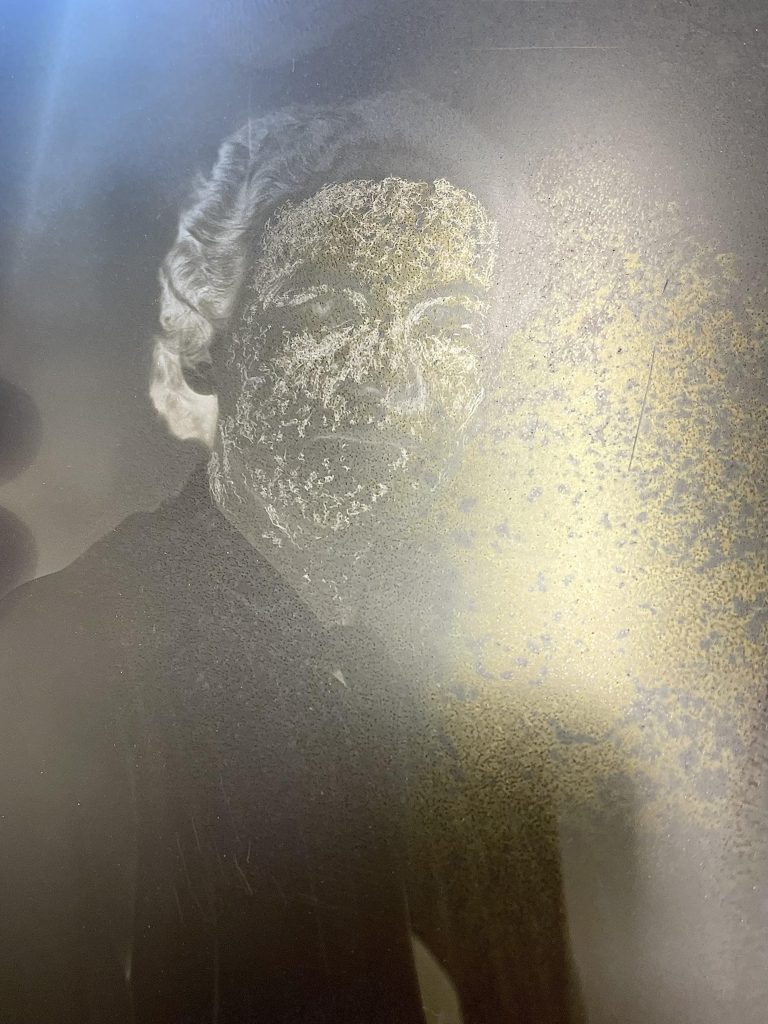

As I made my way through the collection I was repeatedly met with glass plates that possessed faint scratches outlining the contours of a face where wrinkles tend to form, or scribbled dots speckling the skin. I continuously wondered what these etchings might be when I came across a plate that had two negatives of the same woman, but on one she was heavily freckled, and in the other, there was not a spot on her skin to be found. On the emulsion side of the plate, her freckles had been meticulously removed one-by-one with a pointed instrument of sorts to render her skin seemingly airbrushed. I instantly recognized that these “scratches” were an example of the pre-digital age method of “photoshopping” photographs, a technique that Hannah would employ to provide her customers with the option of having a perfect portrait to display.

I had read about the act of manually retouching glass plate negatives in the Victorian era, where the outer edges of a woman’s mid-section were erased to achieve the desired “wasp-waist” look. However, I thought this was an outlying and rare occurrence, but the fact that almost every plate of Hannah’s bears some evidence of retouching shows how common and pervasive this practice was. Furthermore, there was not a specific demographic of Hannah’s client that received this treatment; men and women of all ages, from infants to seniors, were able to take home a photograph of themselves looking their absolute best. Excess stray hairs, deep set wrinkles from decades of emoting, blemishes, freckles, moles, or an accidental hand or prop in the image were all able to be removed by the dedicated photographer’s technique of building up hair-thin lines to erase the undesired.

After doing some research of my own, I discovered that the practice of manually retouching glass plate negatives had been in place since the 1840s, and involved the use of either a graphite pencil or knife to scratch out or cover up whatever it may be that was preventing the desired image. Such retouching appeared almost invisible, both in the glass plate negative and in the final positive. I was able to see evidence of the retouching only when I viewed the emulsion side of the negative from a certain angle where the light could reflect off the scratches. Such a trick-of-the trade exemplifies how not so different we are today from those who lived almost a hundred years ago, and how certain behaviors, such as the editing of photographed portraits, show a formidable continuity over time. I can almost imagine the scene appearing in front of me; Hannah in her studio hunched over a negative, surrounded by various tools and instruments, a soft, rhythmic, scratching noise permeates the air as she works on perfecting her customer’s portrait, the hours ticking by, a radio playing a vintage tune hums in the background, unknowingly creating the plate that would end up in my very hands all these years later.

For further reading on manual retouching of glass plate negatives see https://pastonglass.wordpress.com/2017/11/28/the-art-of-retouching-pre-photoshop/ and https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/83262/how-photo-retouching-worked-photoshop

Alessia Serra

2024-2025 Ringle Conservation Intern

Conservation Services

Tags: Alessia Serra, glass plate negative, Hannah Scott Collection, inventory, Kansas Collection, manual retouching