Manuscript of the Month: Her Book, Written by Her Own Hand

July 27th, 2021N. Kıvılcım Yavuz is conducting research on pre-1600 manuscripts at the Kenneth Spencer Research Library. Each month she will be writing about a manuscript she has worked with and the current KU Library catalog records will be updated in accordance with her findings.

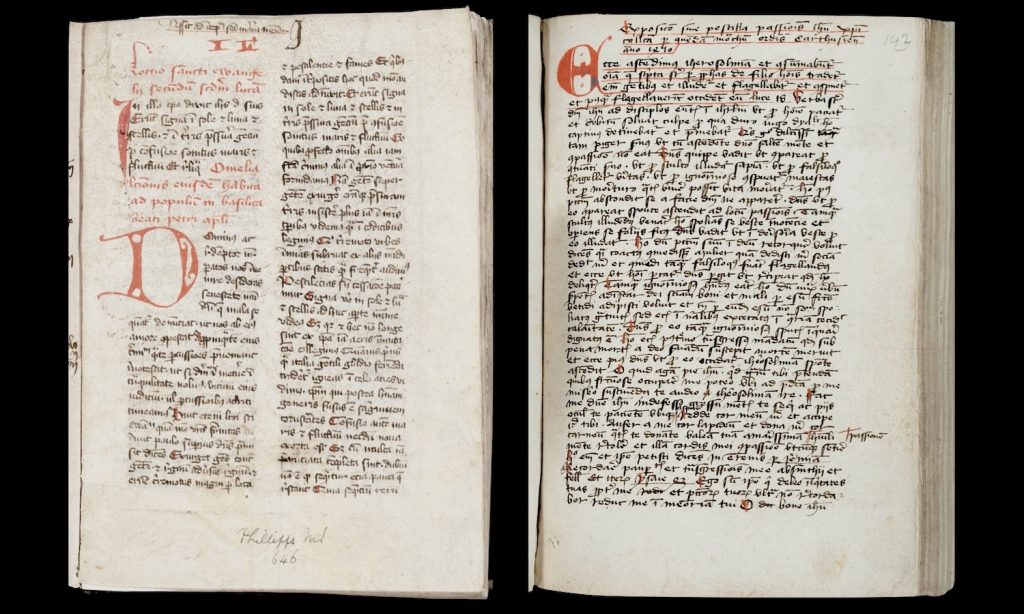

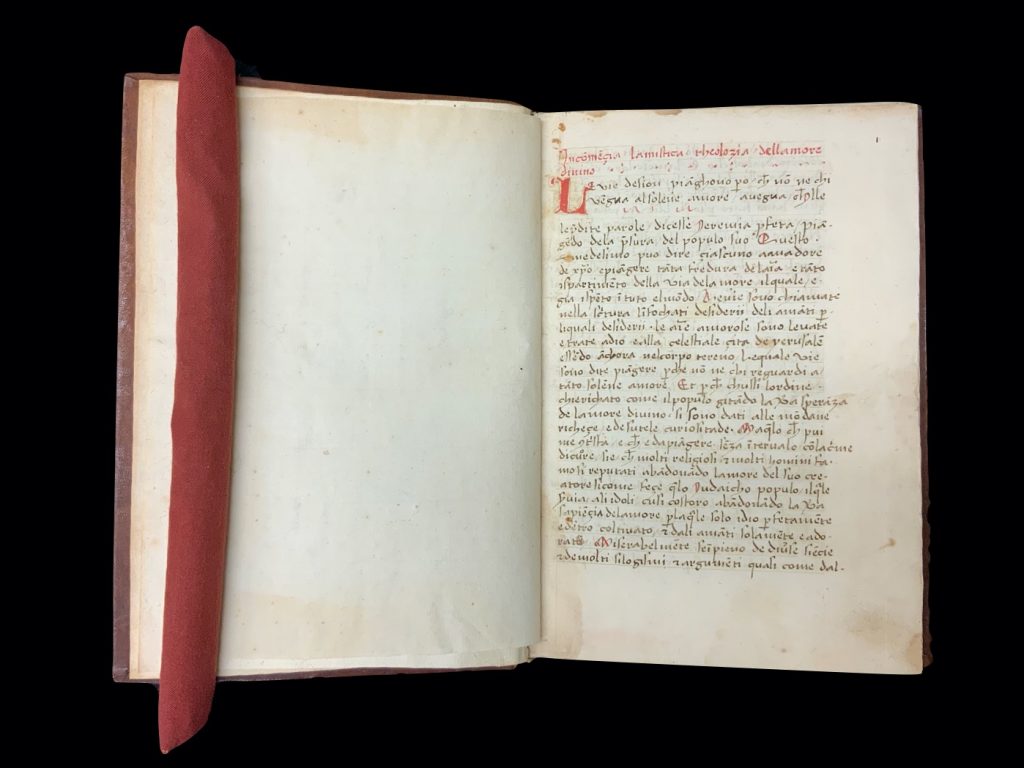

Kenneth Spencer Research Library MS C66 contains a copy of a translation from Latin into Italian of the De theologia mystica [On Mystical Theology], also known by its opening words, the Viae Syon lugent [The Ways of Zion Mourn], along with two much shorter tracts added later. Composed sometime in the second half of the thirteenth century, the exact date of the De theologia mystica in Latin is unknown. Furthermore, its authorship has been subject to debate. In some medieval manuscripts, it is attributed to St Bonaventure, a thirteenth-century Franciscan scholar; however, this is generally accepted to be false. More recently, scholars have argued that the work was composed by Hugh of Balma. Yet, his identity has also been debated. He is now thought to be the same Hugh who was the Prior of the Charterhouse of Meyriat, a Carthusian monastery in Vieu-d’Izenave, France, between 1289 and 1304. The translation into Italian is thought to have been undertaken in or before 1367 by the Jesuit Domenico da Monticchiello. Not much information exists about Domenico either, but he is known also to have translated into Italian the Vita Christi [Life of Christ] by Ludolph of Saxony, another Carthusian scholar. The name of neither the author nor the translator is provided in the copy of the De theologia mystica as we have it in MS C66, where it is indicated only that the work was by a venerable friar of the Carthusian order.

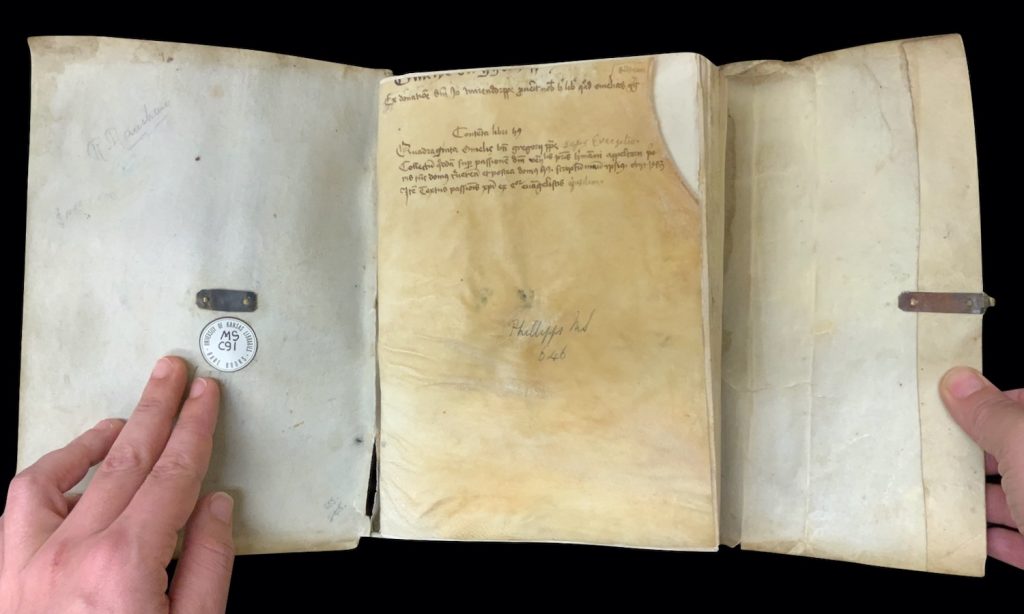

Although Hugh of Balma and his De theologia mystica have received some scholarly attention in recent decades, including a full translation into English in 2002, its medieval Italian translation does not share the same fate. The most recent and the only modern edition is from the mid-nineteenth century, published as part of a series of editions of works by or associated with St Bonaventure. MS C66 was one of the two manuscripts that were used as primary witnesses to the text by Bartolomeo Sorio in this 1852 edition of the De theologia mystica. At the time, the manuscript was part of the collection of Domenico Turazza (1813 –1892), a renowned mathematician considered to be the founder of the School of Engineering at the University of Padua. In this edition, Sorio thanks Turazza for loaning the manuscript to him to study and prepare the edition (p. 54). A note Sorio wrote to Turazza, presumably when he returned the manuscript, is now bound together with the medieval manuscript as part of MS C66.

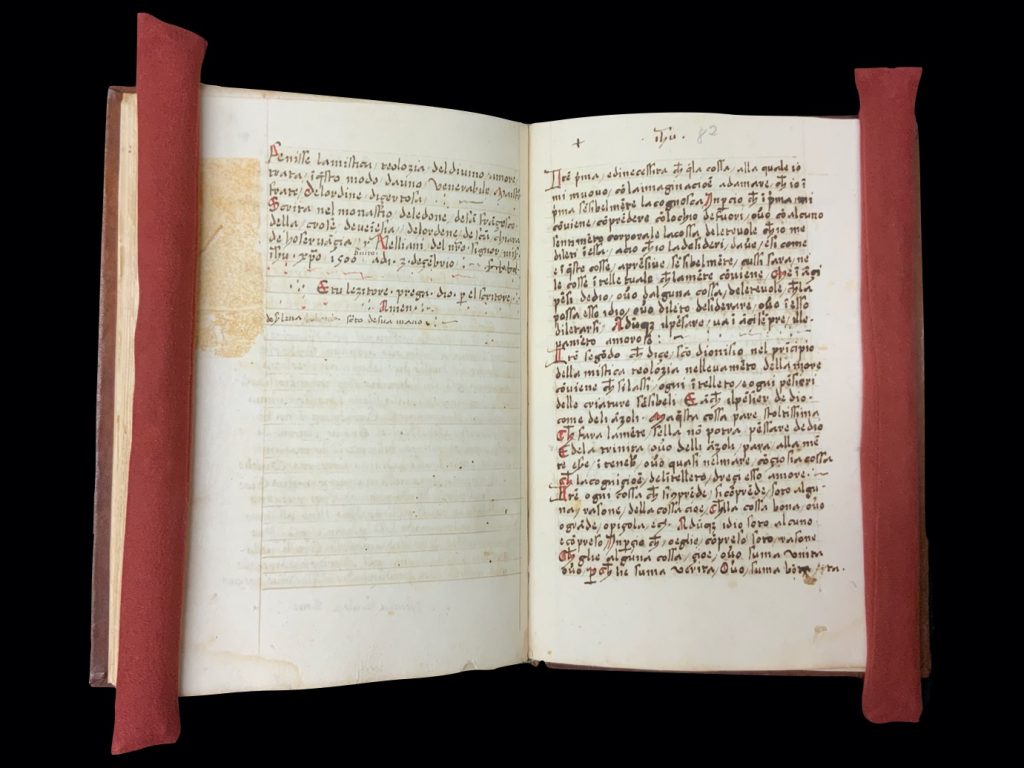

In his edition, Sorio relies heavily on MS C66, especially since the other manuscript he chose was lacking the second half of the work. Despite that, he does not provide much information on the manuscript itself. Although he mentions that the manuscript is dated and the scribe is named at the end of the text, he omits certain details, such as the name of the scribe, not only in his preface but also in the edition of the text. At the closing of the De theologia mystica in MS C66 on folio 81r, the scribe records when and where the manuscript was copied and her name:

Scrita nel monast[er]io de le done de Sa[n] Fra[n]çesco della crose de Vei[n]esia de lordene de S[an]c[t]a Chiara de hoserva[n]çia. Nelliani del n[ost]ro signor mis[er] Ih[es]u Chr[ist]o 1500 finito a di 3 deçe[m]brio. S[uor] Le? Bol?. E tu lezitore prega Dio p[er] el scritore. Amen. De s[uor] Lena […]. Sc[ri]to de sua mano.

Written in the women’s monastery of San Francesco della Croce in Venice of the observant order of St Clare. Finished in the 1500th year of our poor lord Jesus Christ on December 3. Sister Lena […]. And you, reader, pray God for the writer [scribe]. Amen. [The book] of sister Lena […]. Written by her own hand.

Thus, we know that the manuscript was completed on December 3 in the year 1500 in Venice, Italy. Not only that; according to the colophon, MS C66 was copied in a women’s monastery. Although Sorio only mentions that the manuscript was copied by a Clarist nun (“Monaca Clarissa,” p. 29), the nun who copied MS C66 wrote her name on it: sister Lena.

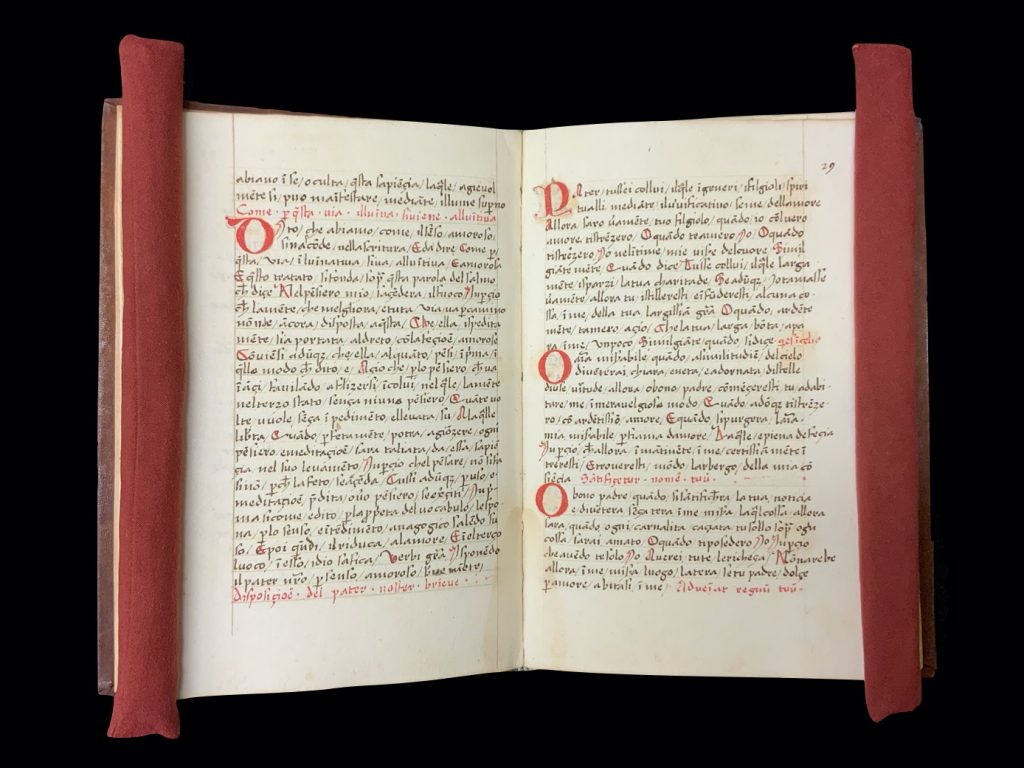

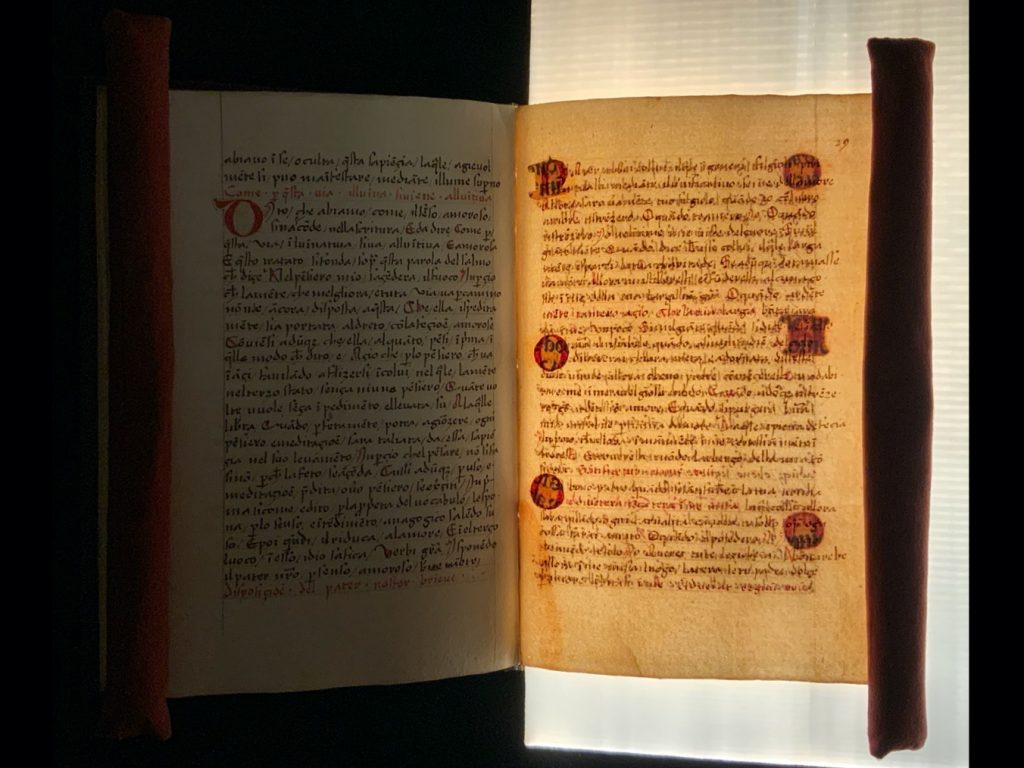

There is another significant, if a little peculiar, aspect of MS C66, which is made of paper. All the initials in the manuscript are cut and pasted from another paper manuscript! More than 200 initials that open each chapter of the De theologia mystica in MS C66 are carefully cut out and placed on the leaves. The initials are all in plain red, made in the same style and they all seem to have originated from a single book. Although Bernard Rosenthal, from whom the University of Kansas acquired the manuscript, wrote in his description that “the initials are painted on small paper slips which are glued into their proper position,” it is certain that these initials were not made for this manuscript but instead repurposed from another one. When the manuscript is examined with a fiberoptic light sheet, which is commonly used for the inspection of watermarks on paper, the text underneath the initials become more apparent. The pieces are too small, however, to identify the text of this other book. I have not noticed any misplaced initials but there are a few instances in which the letter I is pasted upside down. Yet, MS C66 is so meticulously prepared that even this seems like a deliberate choice by sister Lena.

From its contents to its production, MS C66 is an excellent example of the impact of monastic networks in the transmission of texts and knowledge in the Middle Ages. But there is more to it. In his recent book titled Women and the Circulation of Texts in Renaissance Italy, Brian Richardson provides Sister Lena (and MS C66) as an example for his discussion of women scribes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020, p. 101). Many texts from the Middle Ages survive anonymously; their authors are not known. This is also true for medieval manuscripts; we usually do not know who was the parchmenter or the papermaker, the scribe, the rubricator, the illuminator or the binder of a given manuscript. Often, there is a tendency to think that these occupations were assumed by men, and especially that texts were written and copied by men. More and more studies, however, now argue that this may have not been the case. Therefore, it is especially important to bring to light those examples in which one can demonstrate that a medieval manuscript was written and/or decorated by a woman, as is the case with MS C66.

The Kenneth Spencer Research Library purchased the manuscript from Bernard M. Rosenthal Inc. in July 1960, and it is available for consultation at the Library’s Marilyn Stokstad Reading Room when the library is open.

- Edition of the De theologia mystica in Italian based on MS C66: La Teologia mistica attribuita a San Bonaventura, già volgarizzata prima del 1367 da frate Domenico da Montechiello Gesuato, testo di lingua citato dagli accademici della Crusca, ora tratto la prima volta dai Mss. Edited by Bartolomeo Sorio. Verona: Tipografia degli eredi di M. Moroni, 1852. 31-96. [open access]

- Edition of the De theologia mystica in Latin and its translation into French: Théologie mystique. Edited and translated by Francis Ruello and Jeanne Barbet. 2 vols. Sources chrétiennes 408, 409. Paris: Éditions de Cerf, 1995. [KU Libraries]

- Translation of the De theologia mystica from Latin into English: Jasper Hopkins. Hugh of Balma on Mystical Theology: A Translation and an Overview of His De Theologia Mystica. Minneapolis, MN: Arthur J. Banning Press, 2002. [open access]

N. Kıvılcım Yavuz

Ann Hyde Postdoctoral Researcher

Follow the account “Manuscripts &c.” on Twitter and Instagram for postings about manuscripts from the Kenneth Spencer Research Library.