The Confederate States of Plants

June 3rd, 2016Much as Martha Stewart sought to guide the American home-makers of the 1980 and 1990’s through the intricacies of family care and entertaining, so were authors such as Sarah Rutledge endeavoring to do over one-hundred years earlier. Rutledge published The Carolina Housewife by a Lady of Charleston in 1847 to provide her contemporaries with “receipts for dishes that have been made in our own houses, and with no more elaborate abattrie de cuisine than that belonging to families of moderate income” (Rutledge, p. iv, 1979 edition). As a longtime reader of books related to cooking and the domestic arts, I have observed that writers of these tomes feel a fierce pride about their local flora, fauna, and the manner in which these things are combined to create meals. Additionally, they often feel it is their duty to give instruction to the readers that as keepers of home and family; they are also guardians of the physical and moral well-being of the body of their community and even their nation.

KSU

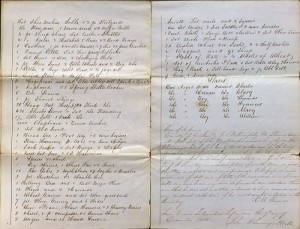

While researching Rutledge’s book, I was pleased to find the work of a contemporary in the Spencer Research Library collection. While not strictly a cookbook, Resources of the Southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural, by Francis Peyre Porcher, fits nicely within the domestic economy genre. Porcher, a physician for the Confederacy during the Civil War, was granted a stay from service to write and publish this “Hand-book of scientific and popular knowledge, as regards the medicinal, economical and useful properties of the Trees, Plants and Shrubs found within the Southern States, whether employed in the arts, for manufacturing purposes, or in domestic economy, to supply for present as well as future want” (p. v, 1869 edition). The contents of its nearly 800 pages are a rich repository of botanical information, important today as they describe many plants now extinct or nearly so, including the much-beloved heirloom grain, Carolina Gold Rice.

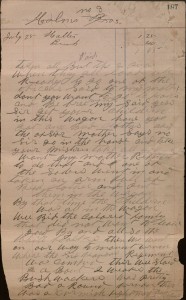

Title page (l) and text page (r) of Resources of the

Southern Fields and Forests

(Charleston: Walker, Evans & Cogswell, 1869).

Call Number: C6678 item 1. Click images to enlarge.

It is in Porcher’s introduction to the Spencer’s 1869 edition, though, that we gain a peek into some less than botanical thoughts running underneath this seemingly straightforward text; those being about the abolishment of slavery and its effect on the southern states. The 1869 introduction is seven pages longer than the 1863 edition (written during the war), much of its added length owing to Porcher’s description of how the south’s many swamps and bogs must continue to be converted into farmable land. This was work that until emancipation, had been carried out by African and African-descent people held in slavery in the southern states. He writes, “[i]t is true that much of this work was done under the system of primogeniture, when it was in the power and to the interest of the owner of the soil…to look for the permanent welfare of his descendants.” While not mentioning slavery, Porcher seems to imply that the “owner of the soil” also “owns” the workers of the soil. Porcher acknowledges that the task of reclamation will be impossible without governmental assistance.

In his final paragraphs, he writes, “the State; which should, when it becomes necessary, perform for its citizens those acts of public utility, the right or ability to do which depended on systems and institutions which it has, from reasons of policy or interest, abolished or destroyed, and being deprived of which, they suffer” (p. xv). Once again, Porcher does not mention slavery directly, but instead uses the word “institution” in its place. The idea of slavery being an institution was first made popular by the South Carolina statesman, John Calhoun, when he spoke of it as the South’s ‘peculiar domestick(sic) institution’. Though veiled in euphemism, Porcher makes clear that he believes that the end of slavery is a punishment for the southern states; a punishment by which “they suffer”. This deprivation renders its population unable to protect its physical and moral interests.

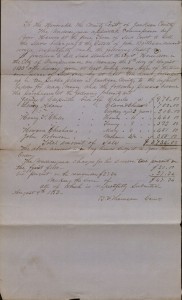

Advertisement page from

Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests, 1869.

Call Number: C6678 item 1.

Click image to enlarge.

Roberta Woodrick

Assistant Conservator, General Collections

Conservation Services