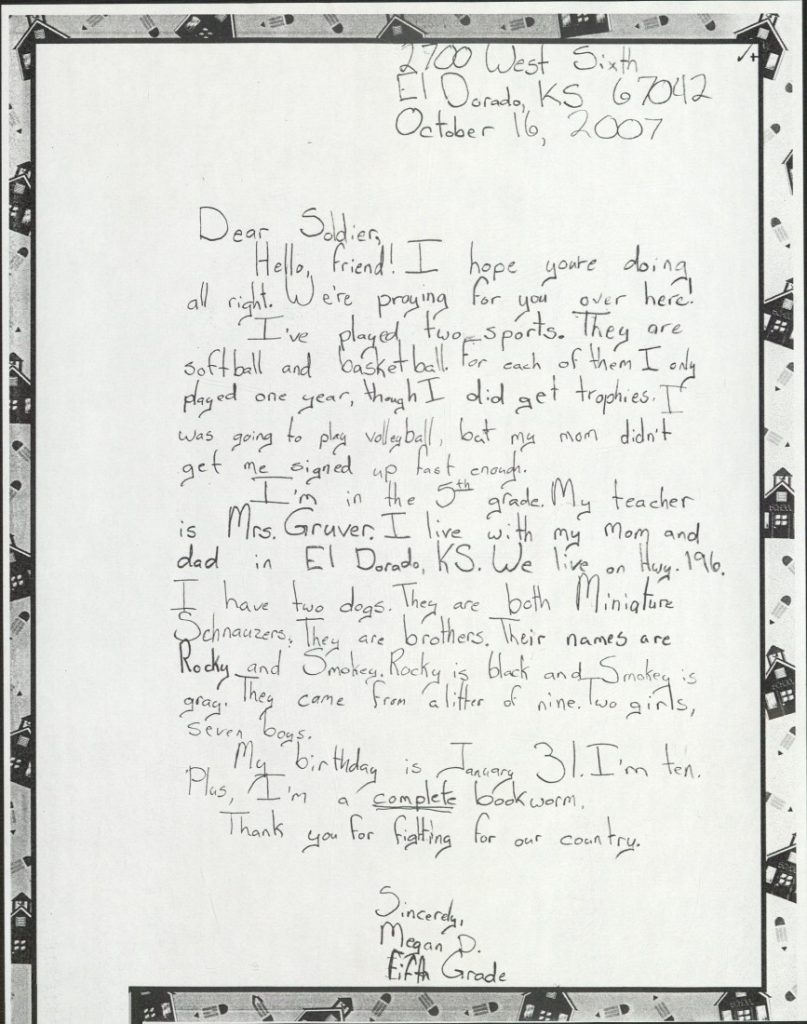

Dear Soldier

October 15th, 2021In the fall of 2007, Air National Guard Sergeant William Leggett was doing his laundry. He was serving a third tour of duty in the Middle East, this time in Iraq. As he walked past a trash bin, he glanced into it and saw a large envelope addressed “To Any Soldier.” Never one to resist a possible trash treasure, he opened the envelope to find a packet of “Dear Soldier” letters, written by fifth- and sixth-grade students from Oil Hill Elementary School in El Dorado, Kansas.

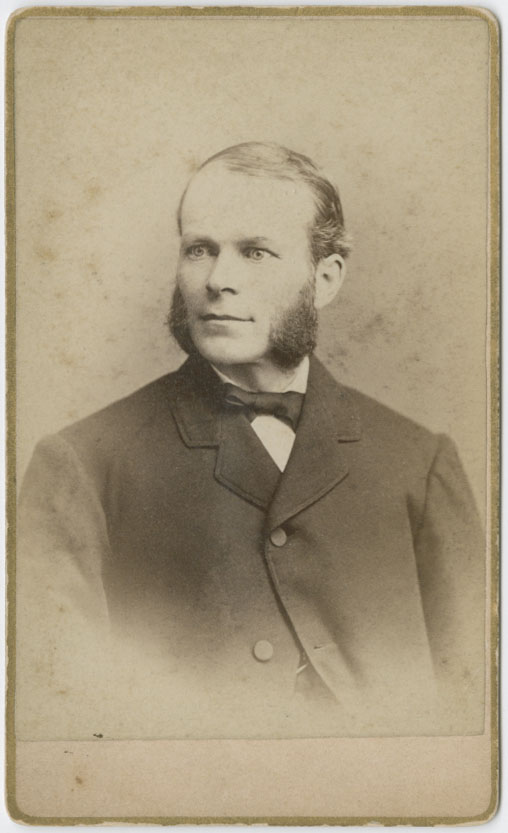

Sergeant Leggett was my brother, five years younger than me. From this point on I will call him Bill. Growing up together in Pennsylvania, he was the typical little brother. He chased me with Cicada shells from his bug collection, ditched me when we had chores, and announced on the school bus that I wore flowered underwear. On long car rides, he annoyed me by looking out of my window or breathing on me.

Nevertheless, we were close, despite our age difference. We made bike ramps out of old scrap wood our Dad had in his workshop, and we rode our bikes up and down our long driveway, trying to best each other’s jumps. I taught him how to make a bridge for his Tonka toys out of books and a rug, but he sometimes forgot the “trick” for getting the books to stay in place, so he asked me to show him again…and again…and again. We played baseball, taking turns pitching. On some of those long car rides, if I was feeling a little motherly and he didn’t smell too badly, I let him put his head on my lap to sleep (this was before seatbelts laws). He shared a bunk bed with our youngest brother, and many nights, after he had gone to bed, I heard him crying over something. We talked it out until he felt better, while I stood on tip toes on the bottom bunk. After I moved away, we wrote letters to each other throughout the rest of his childhood. I still have them.

Bill lived in Pennsylvania, with his family. He had been to Kansas to visit me a few times, and I saw him whenever I went to Pennsylvania. But we didn’t see each other, or have opportunities to talk, very often. He called me on my birthday and sang to me, badly on purpose. I wish I would have kept at least one of those voicemails. While he was in Iraq, we emailed each other almost every day. It was wonderful to talk again. He told me about the packet of letters he had found. I was excited to learn that the school was in Kansas, just off I-35, only two hours from my house.

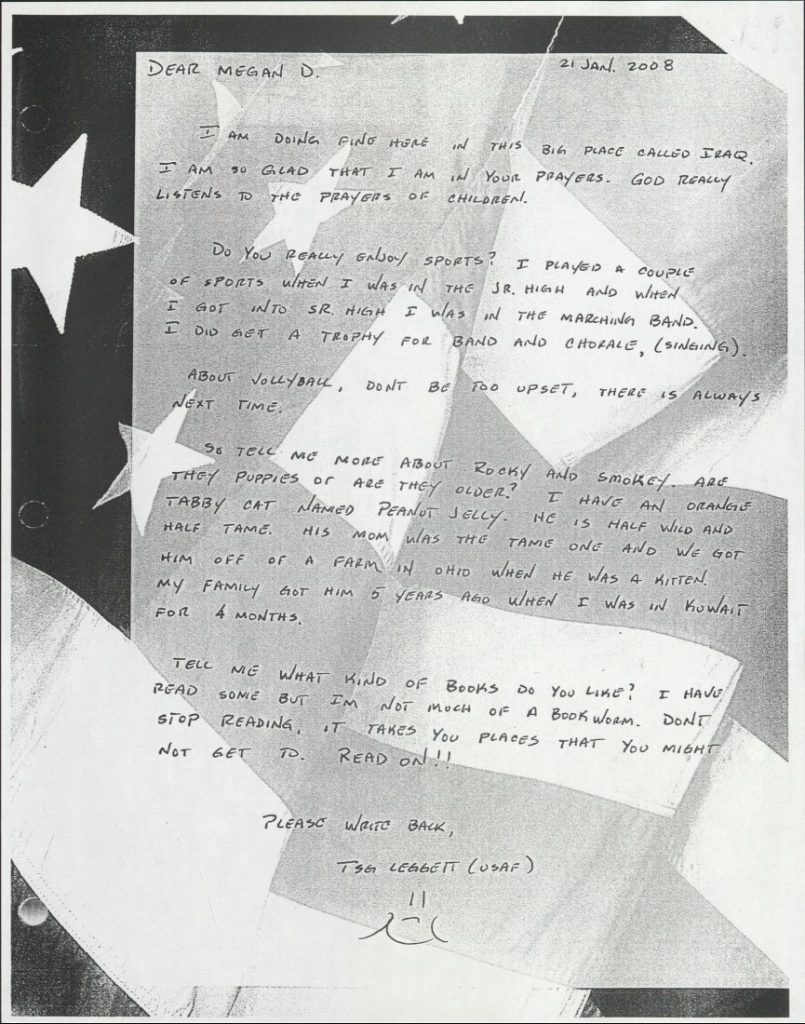

He told me that he planned to hand-write letters to each student, individually. While I found it rather over the top that he would actually take the time to respond to each child, rather than just writing to the class as a whole or using email, I wasn’t surprised that he would do that. He told me that he felt the students deserved individual letters because THEY were the ones who had written individual letters in the first place, and it would be a shame if they each didn’t get a response. Besides, it gave him a project to pass the time.

So, for the rest of his tour of duty, he wrote to them, and they wrote back. He asked them to call him Bill. The students wrote of family members, pets, favorite sports, and things of childhood and school. They sent him artwork. They asked Bill questions about his life, what it was like to be in the military, and what his favorite things were. They closed by asking him to please write back. Bill wrote about his boys, Peanut Jelly the cat, and NASCAR. He described Iraq, its people, and the places he had been. He talked about life in the military, his job, and things like what food the soldiers ate. He wrote of what he missed back home. In each letter, he made sure to include encouragement. He reminded the students to do their best, to study hard, and to pursue their dreams. And he often included a smiley face when he signed off.

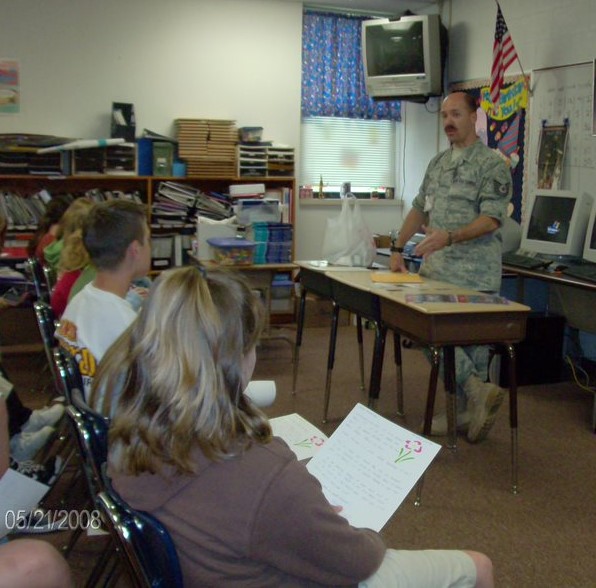

As the time to come back to the States got closer, Bill and I started talking about a visit to Kansas and the school. I contacted the teacher who had given the letter writing assignment about the possibility, and she took it from there. All we had to do was get him there. The visit was a surprise for the students, and it went beautifully. He hand-delivered his last letters, gave out some gifts he brought back from Iraq, held a question/answer session, played basketball with them at recess, and ate lunch with them. Students had their picture taken with him. He was presented with a school t-shirt and a flag that had been signed by the students and teachers. Bill was treated like royalty. When he left, there were hugs and tears, and promises to keep writing.

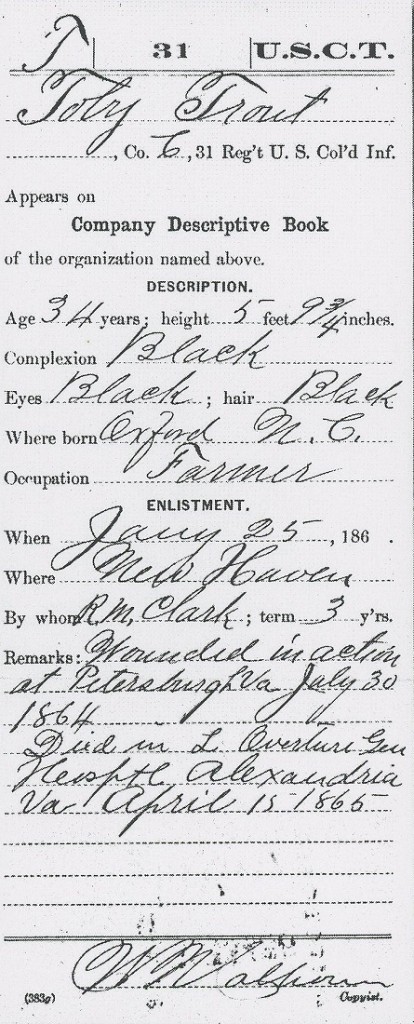

The students are in their mid-twenties today. They probably don’t know that Bill has passed. He died in 2020, in a work-related accident, just fifty-five years old. I hope they know, or someday know, that their letters are now the “Sergeant William J. Leggett Correspondence with Students of Oil Hill Elementary School, El Dorado, Kansas” collection, in Kenneth Spencer Research Library. When I asked Bill if I could make copies of the letters and donate them, he asked me why anyone would be interested in them. I explained that the best parts of the collections in Spencer are the personal stories that put history in context and make it real. He wasn’t convinced, but he let me do it anyway. He kept the originals because he wasn’t ready to part with them yet. I believe the letters meant as much to him as they did to the students.

Kathy Lafferty

Public Services