The Search for Women’s Suffrage: Re-Discovering Letters from Susan B. Anthony

September 3rd, 2019To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment (which prohibits states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to U.S. citizens on the basis of sex), the Public Services staff at Kenneth Spencer Research Library are exploring the collections to create a list of materials in our holdings related to this historic event.

This summer, I served as a temporary Reference Specialist in Public Services. One of my primary projects in this role was to seek out women’s suffrage-related materials specifically within the University Archives division of the Library, which documents the history of the University of Kansas and its people.

This project required a good deal of patience and persistence, as it is not always clear whether a collection contains suffrage materials based solely on its title or even on its digital finding aid. As a result, often the best way to be certain of a potentially-promising collection’s contents was to go through them folder by folder, item by item.

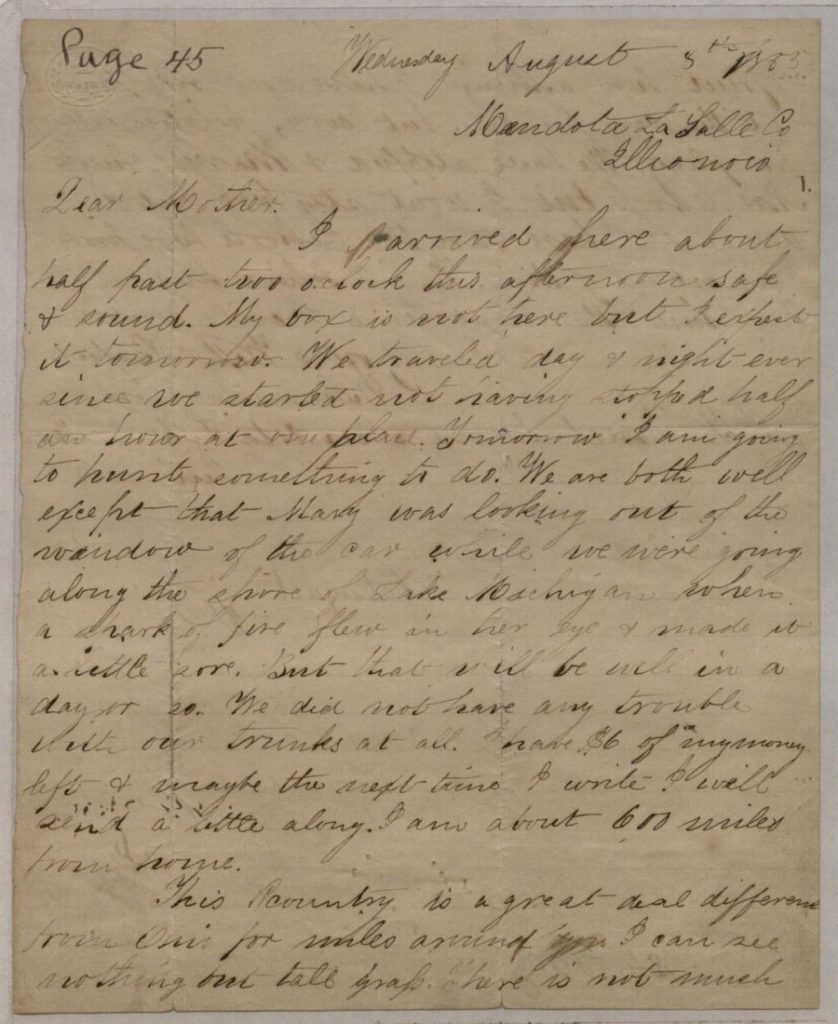

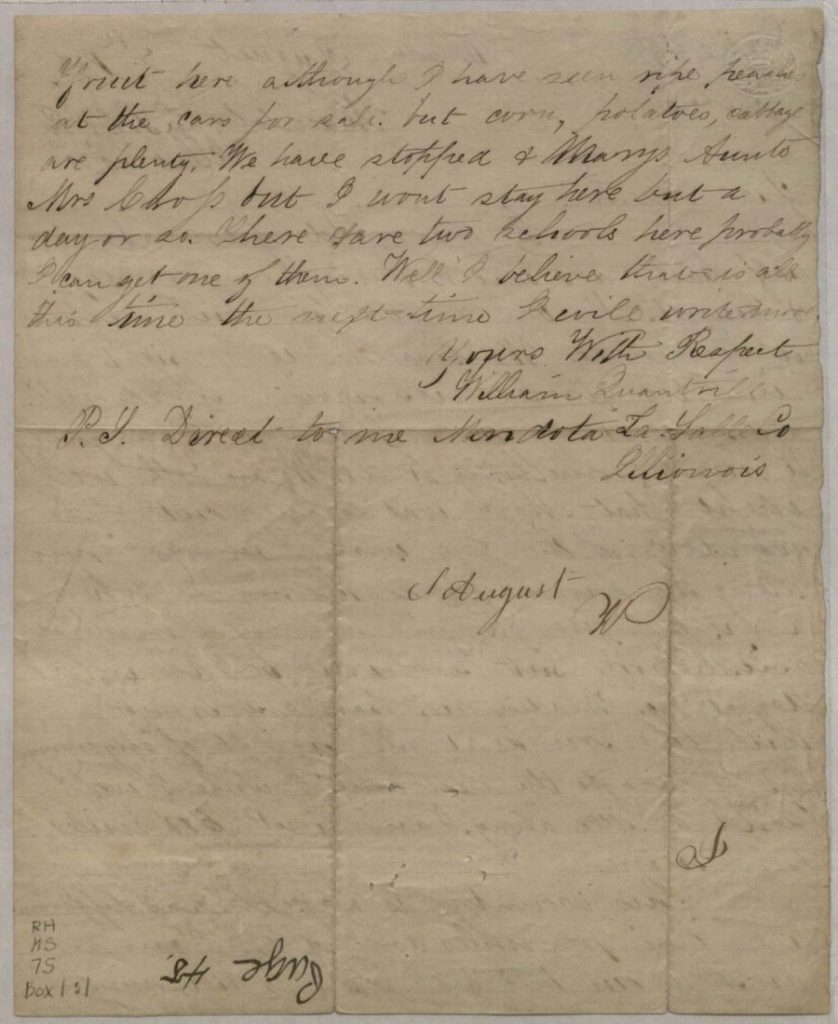

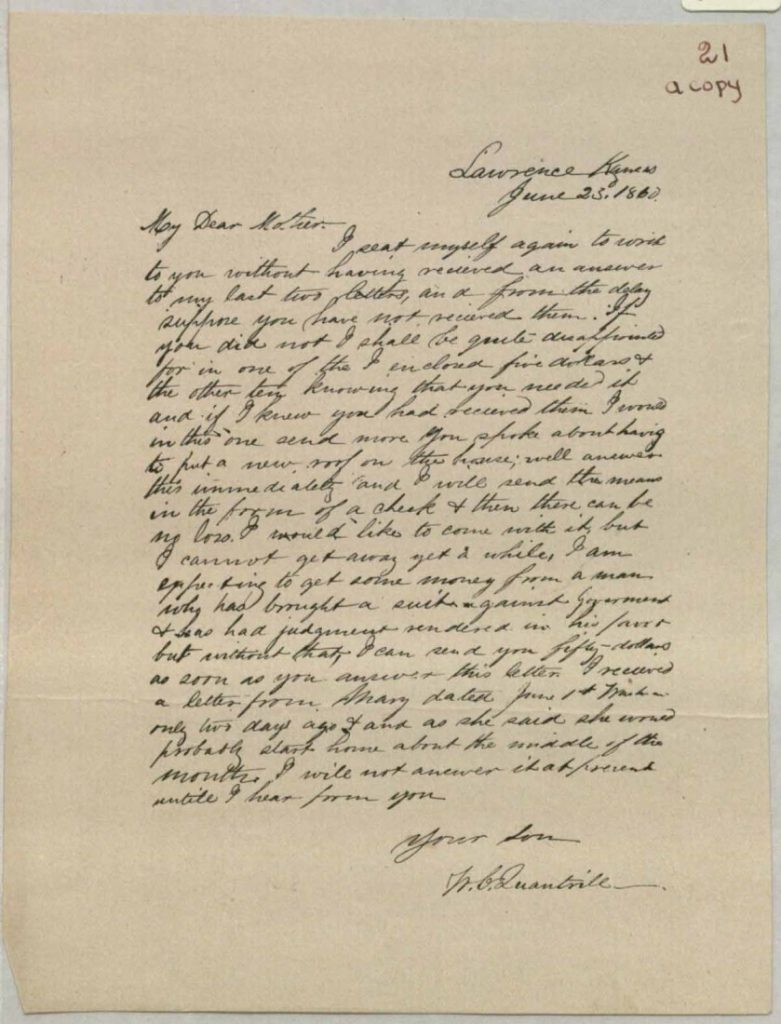

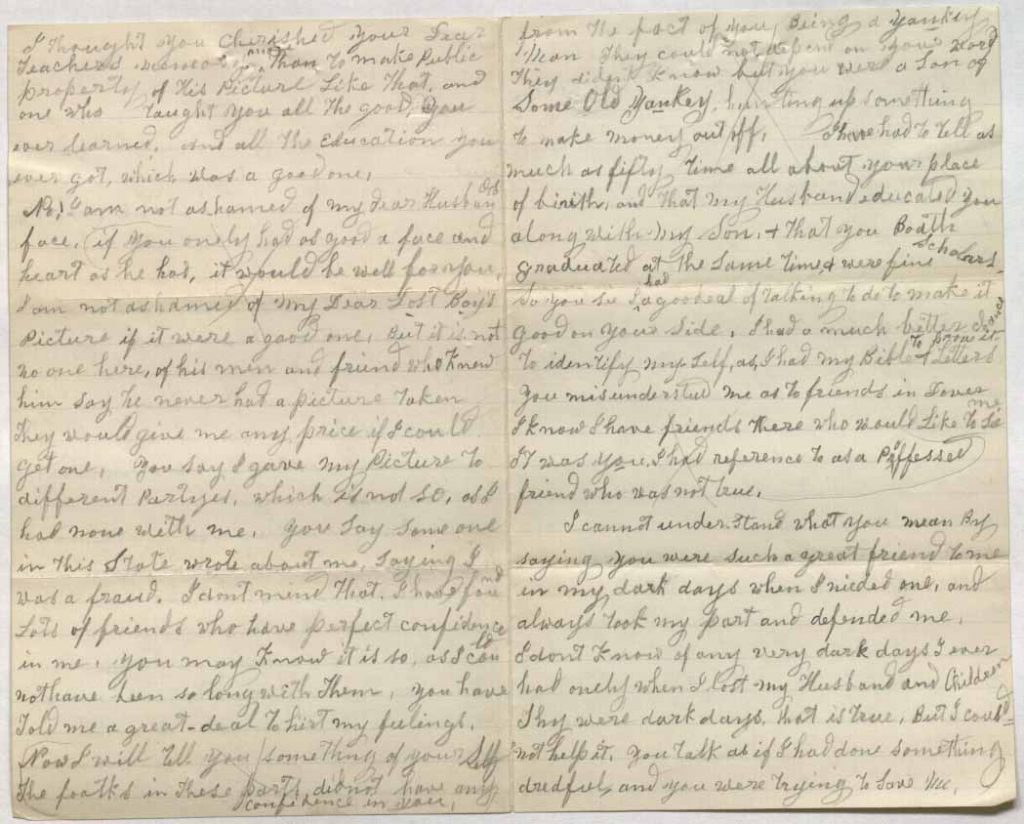

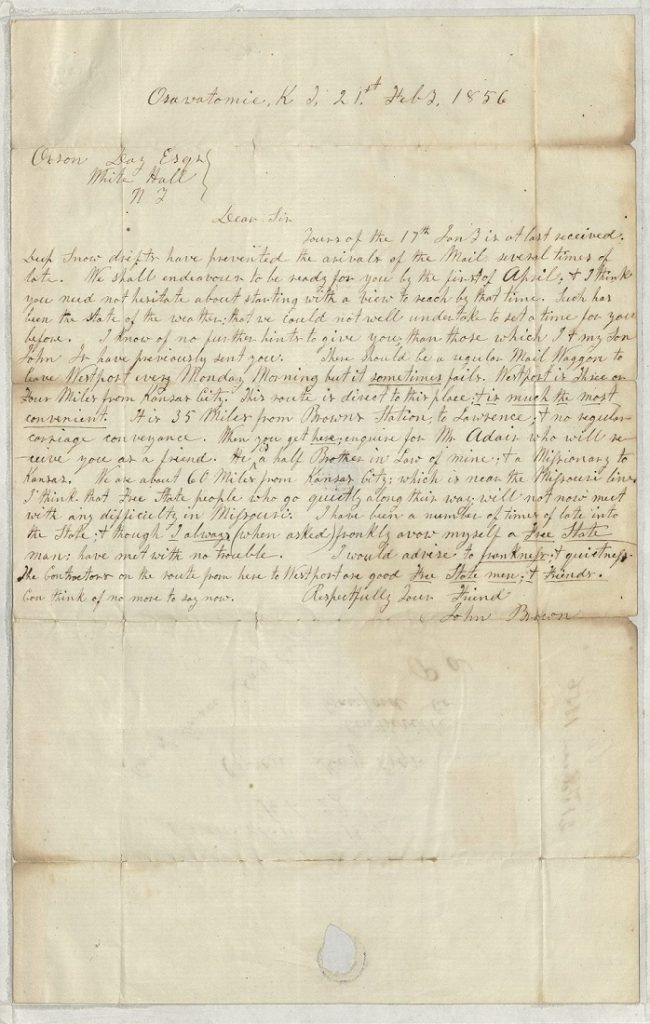

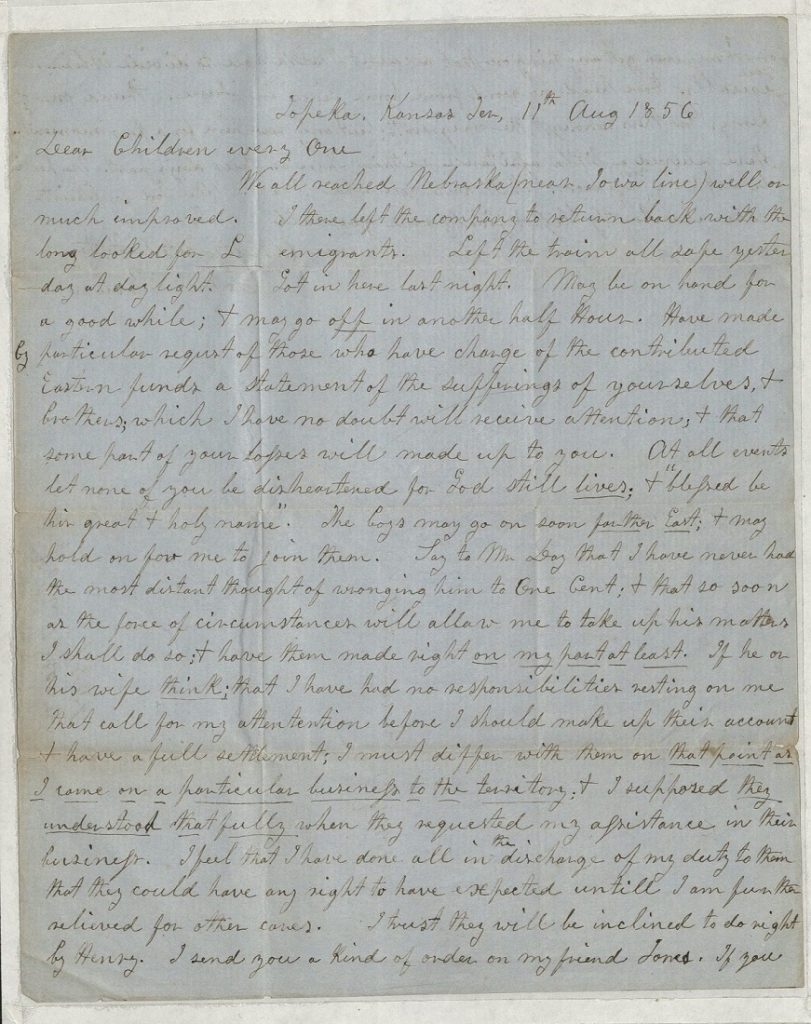

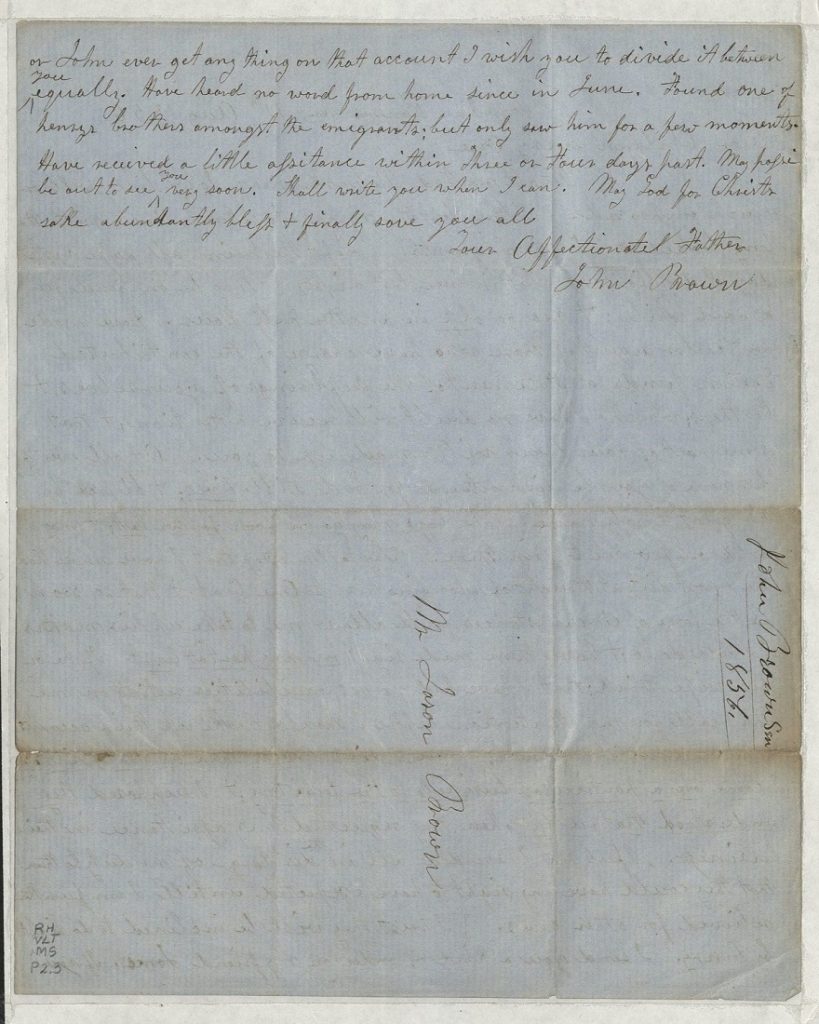

My most exciting find came from the Kate Stephens Collection (PP 43). In Box 2, I came across seven letters written to Stephens by noted women’s suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony.

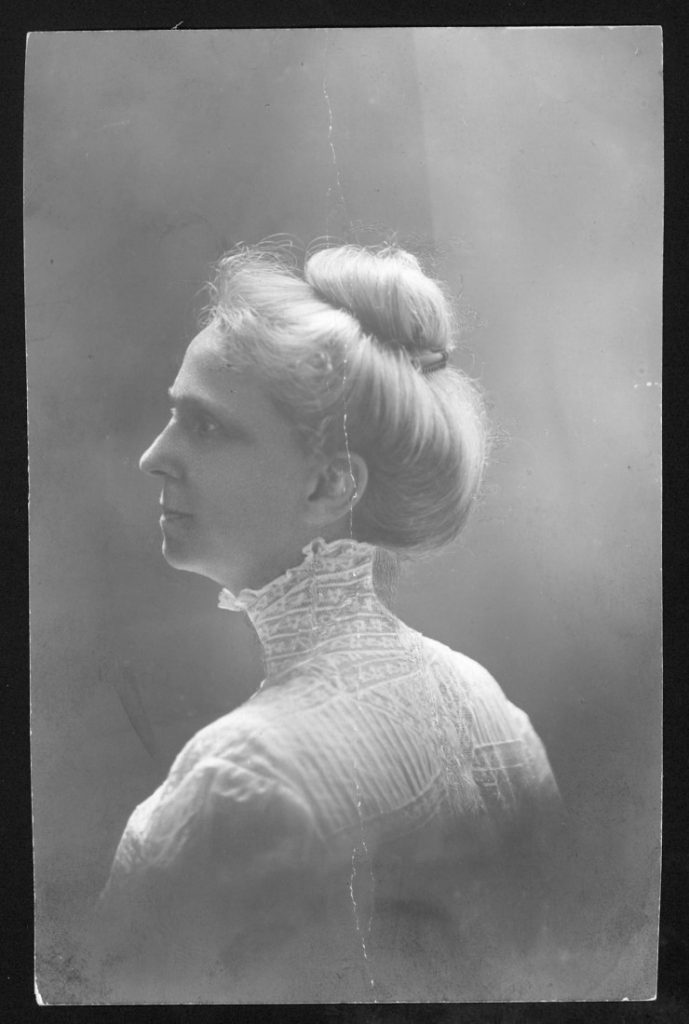

Stephens, a Professor of Greek at KU in the late 1870s and 1880s, was the first woman to serve as the Chair of a department at the university. Stephens was asked to resign from her position in 1885, a decision she appears to have attributed to her gender, her lack of religious affiliation, or possibly the recent death of her father, a prominent lawyer and judge. However, Stephens went on to become a prolific writer, editor, and proponent of women’s equality in higher education.

Box 2 of Stephens’ collection contains correspondence, though further details (such as dates or senders of this correspondence) were not previously provided in the collection’s finding aid. As such, I was surprised and thrilled to find the box contained letters from Susan B. Anthony.

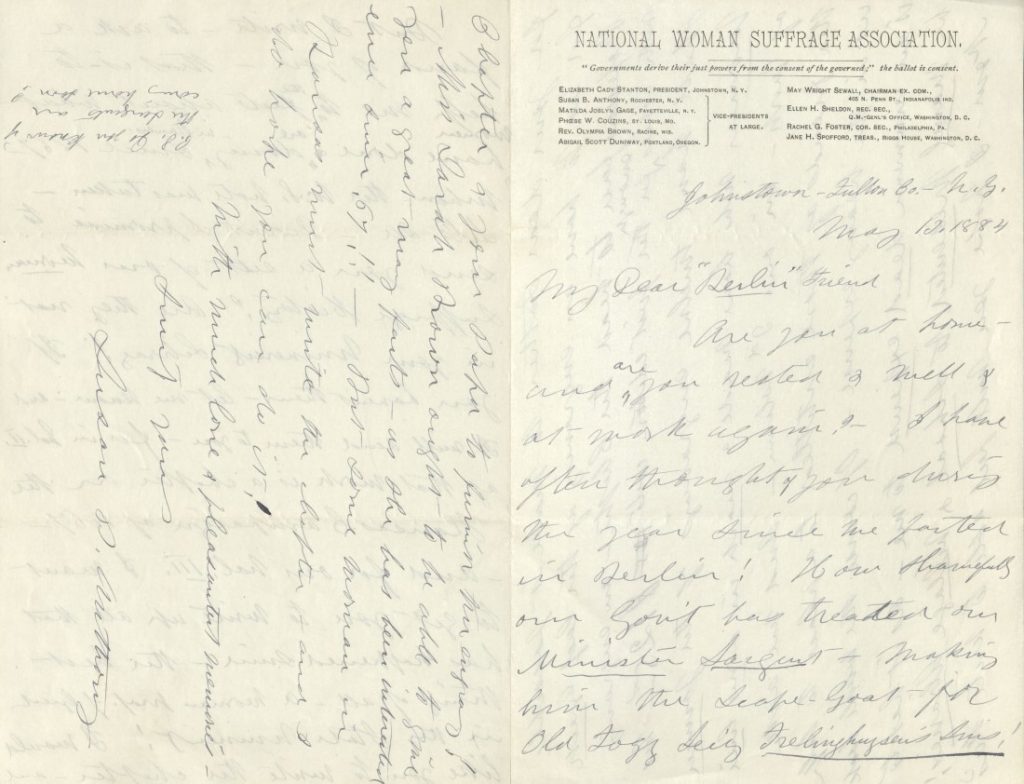

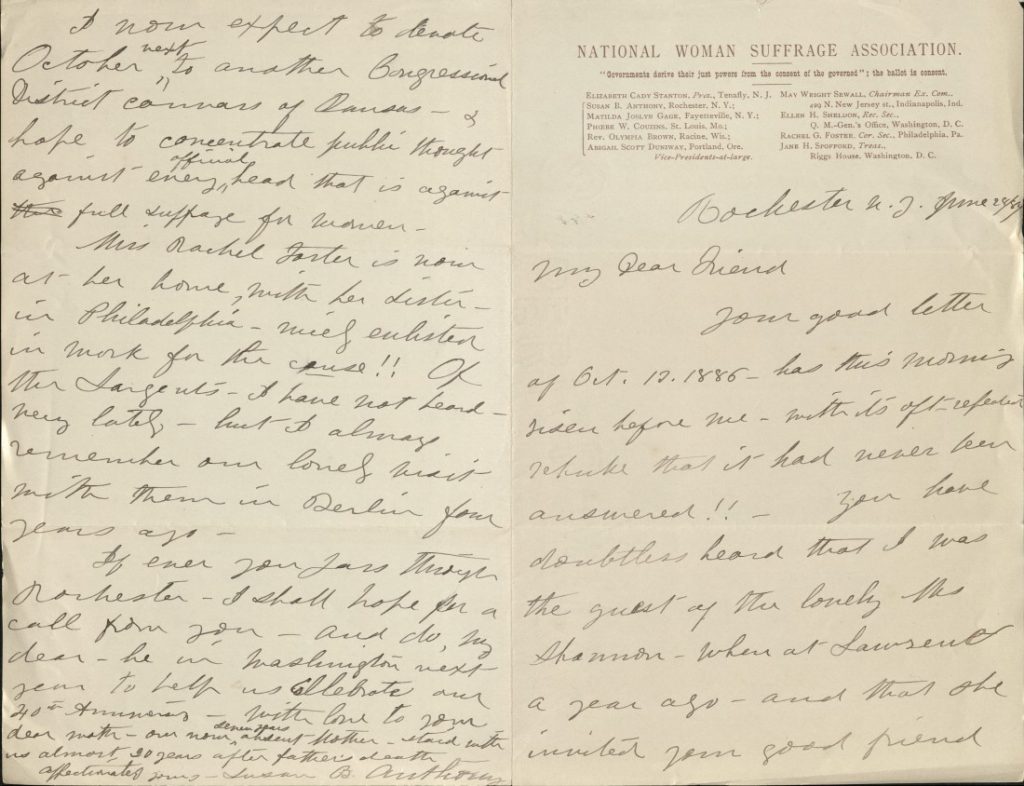

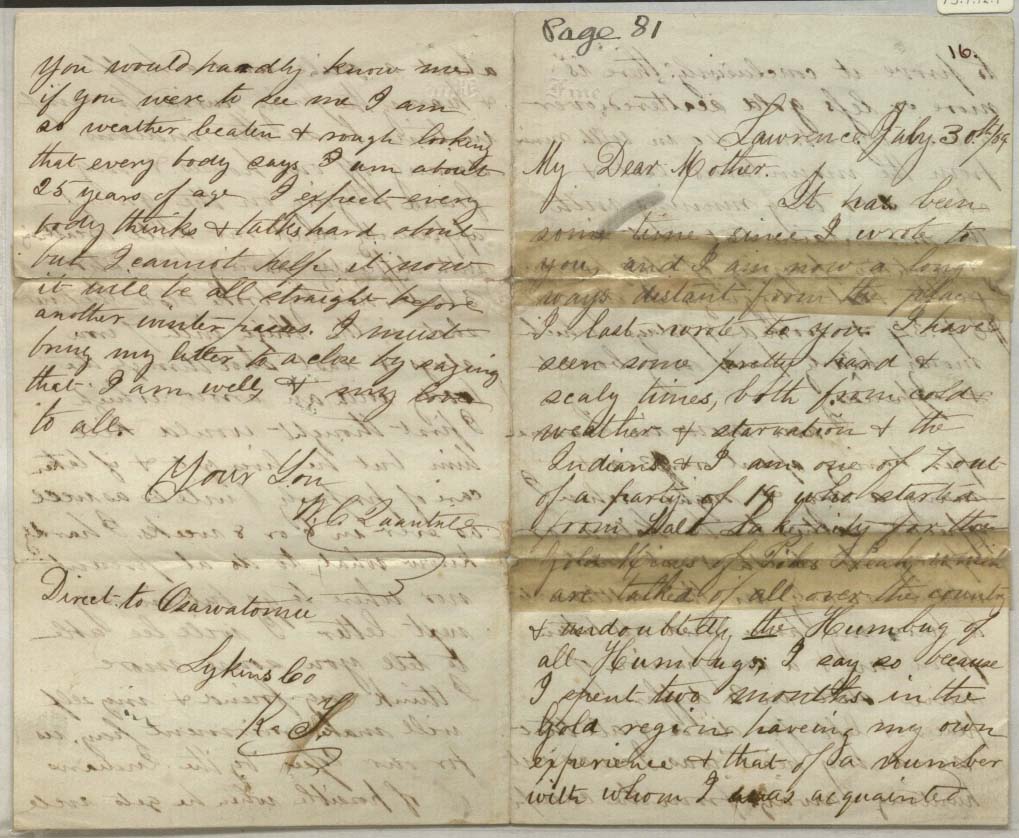

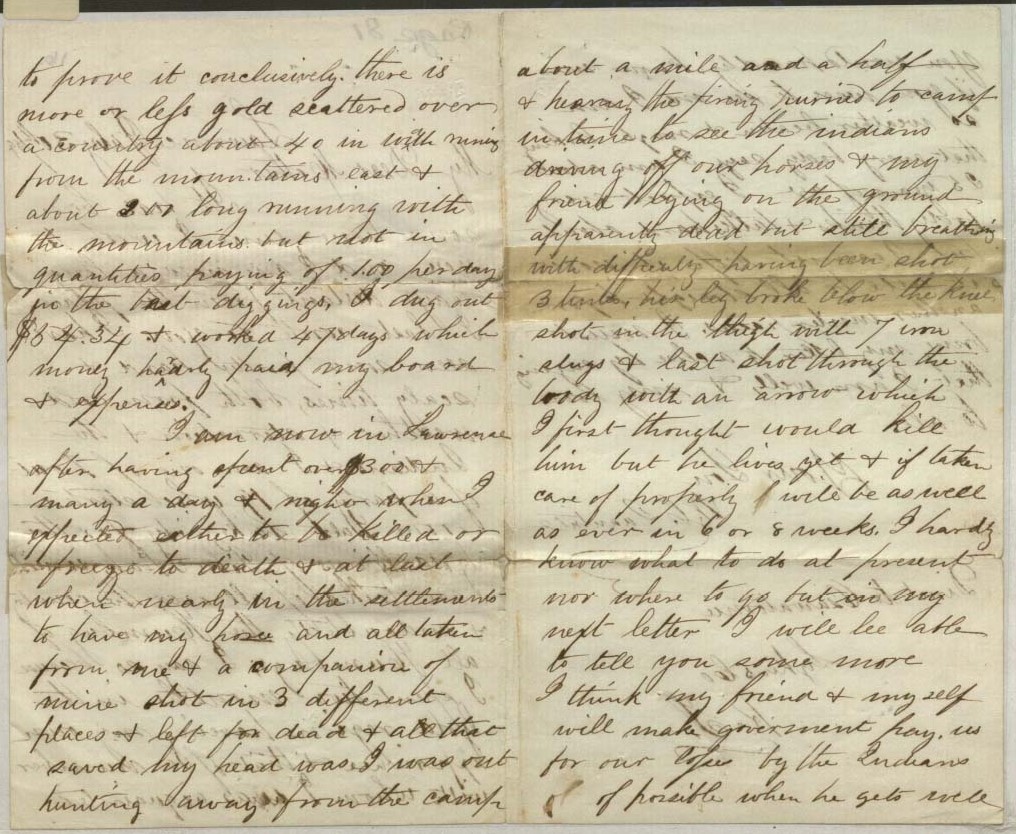

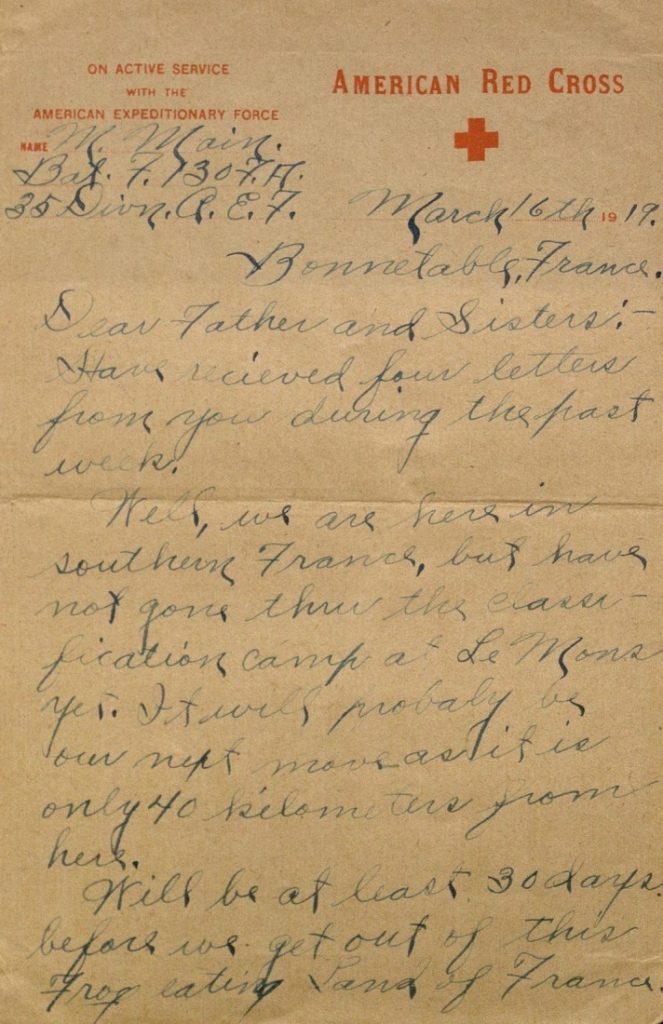

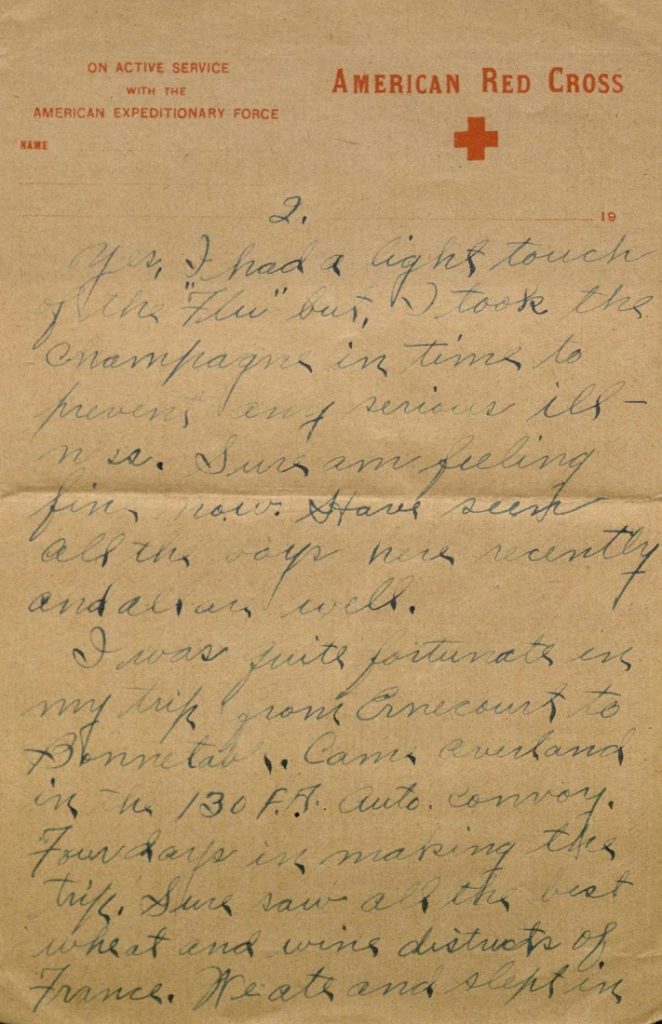

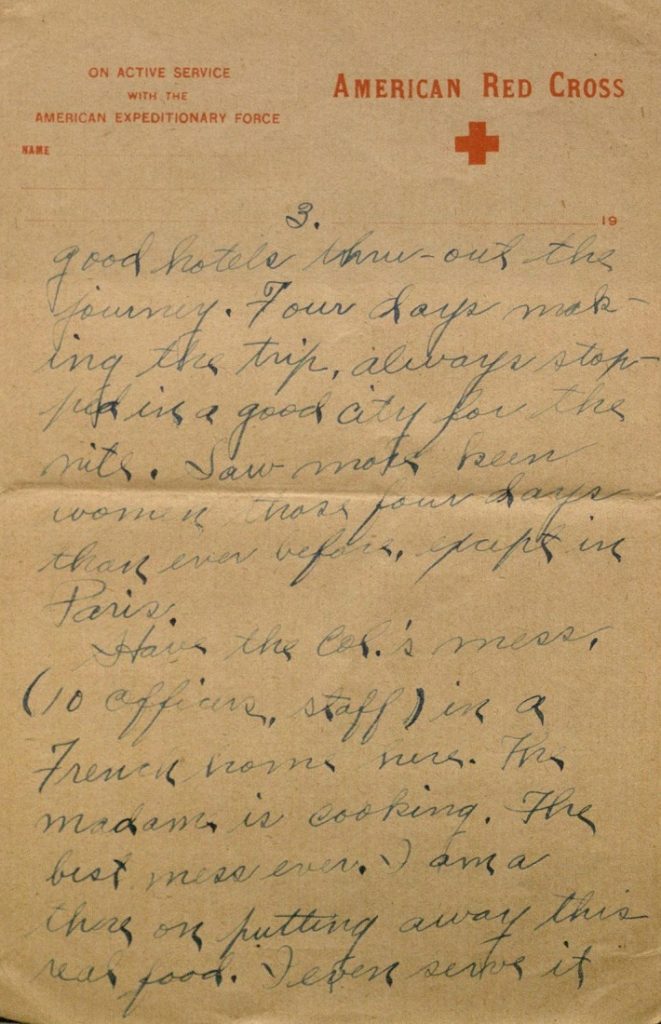

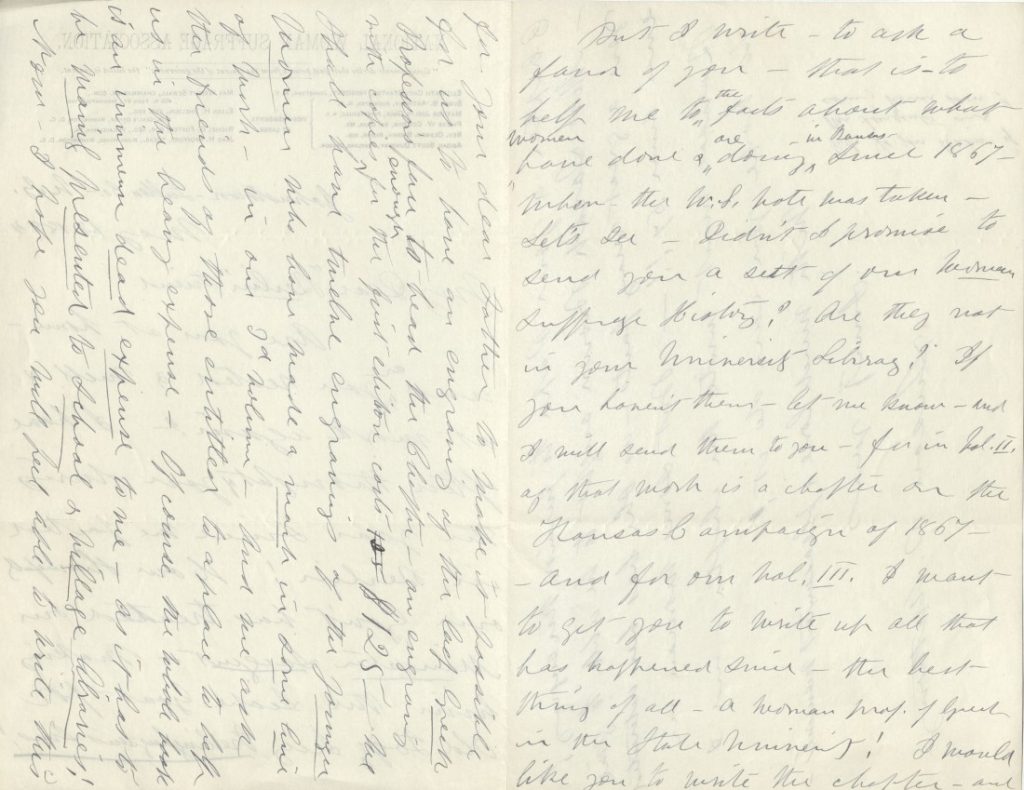

Written on letterhead for the “National Woman Suffrage Association” and dated between 1884 and 1888, the letters build on an existing relationship between the two women that appears to have begun years earlier when Stephens served as a translator for Anthony’s lectures in Berlin, Germany. In some instances, Anthony’s writing is social, such discussions regarding shared acquaintances or regarding Anthony’s niece, who she hoped to persuade to attend KU.

In other instances, the contents of Anthony’s letters relate directly to the fight for women’s right to vote. For instance, Anthony asks Stephens to write a chapter in the forthcoming third volume of History of Woman Suffrage (a task Stephens attempted but was not able to complete) and to help organize a Women’s Suffrage Convention in Lawrence (which was held on November 1-2, 1886).

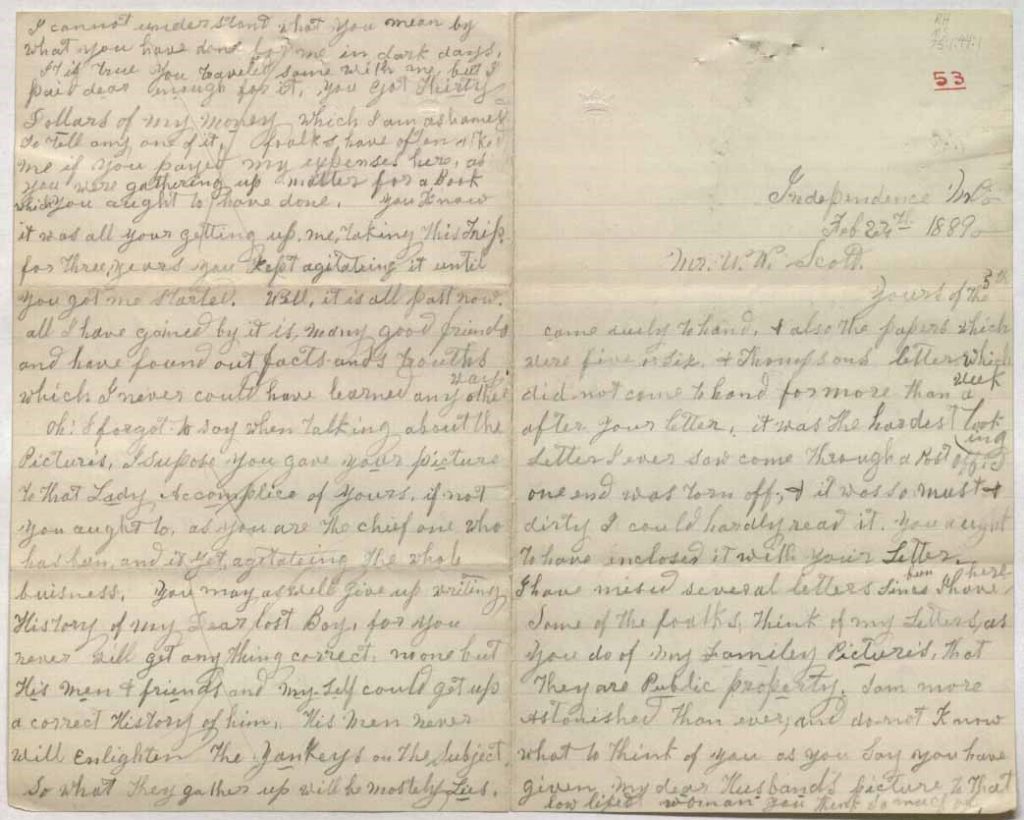

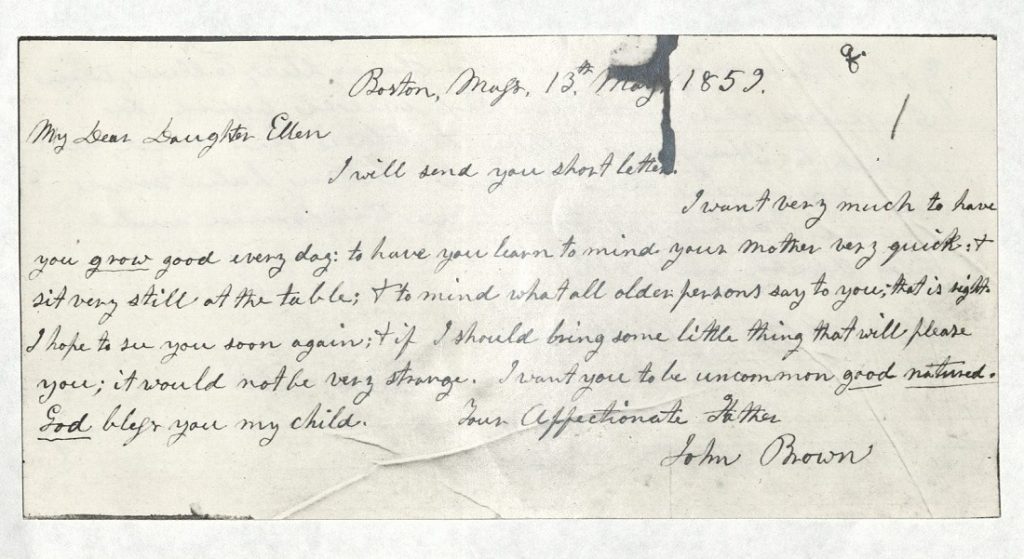

Anthony’s letters also demonstrate her interest in Stephens’ career, expressing congratulations when Stephens becomes a full professor and speculating on the motivations for Stephens later being asked to resign. As to this last event, Anthony wrote to Stephens on June 28, 1887:

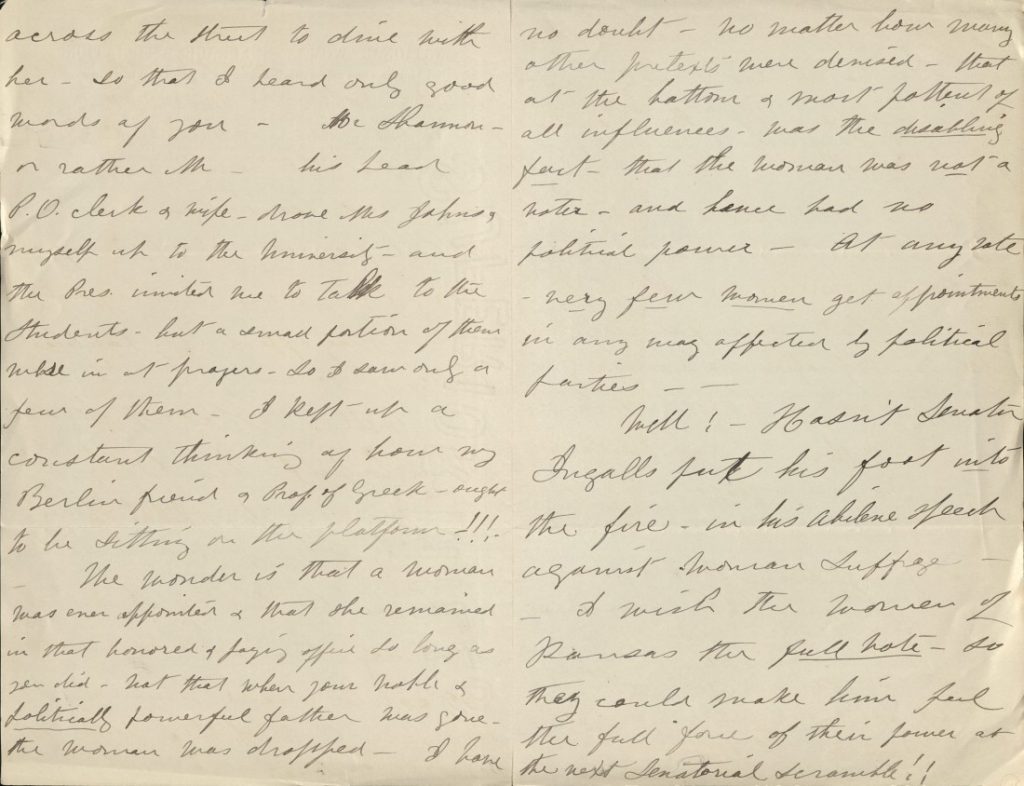

The wonder is that a woman was ever appointed & that she remained in that honored & […] office so long as she did – not that when your noble & politically powerful father was gone the woman was dropped – I have no doubt – no matter how many other pretexts were devised – that at the bottom & most pottent of all influences – was the disabling facts – that the woman was not a voter and hence had no political power […]

As these letters from Anthony to Stephens were undocumented in the collection’s finding aid, there was previously no definitive way to learn of their existence. Their re-discovery has been noteworthy, not only for the commemoration of women’s suffrage, but also for prompting a revision of the collection’s cataloguing to help ensure future researchers can find and access them in years to come.

Sarah E. Polo

Reference Specialist

Public Services