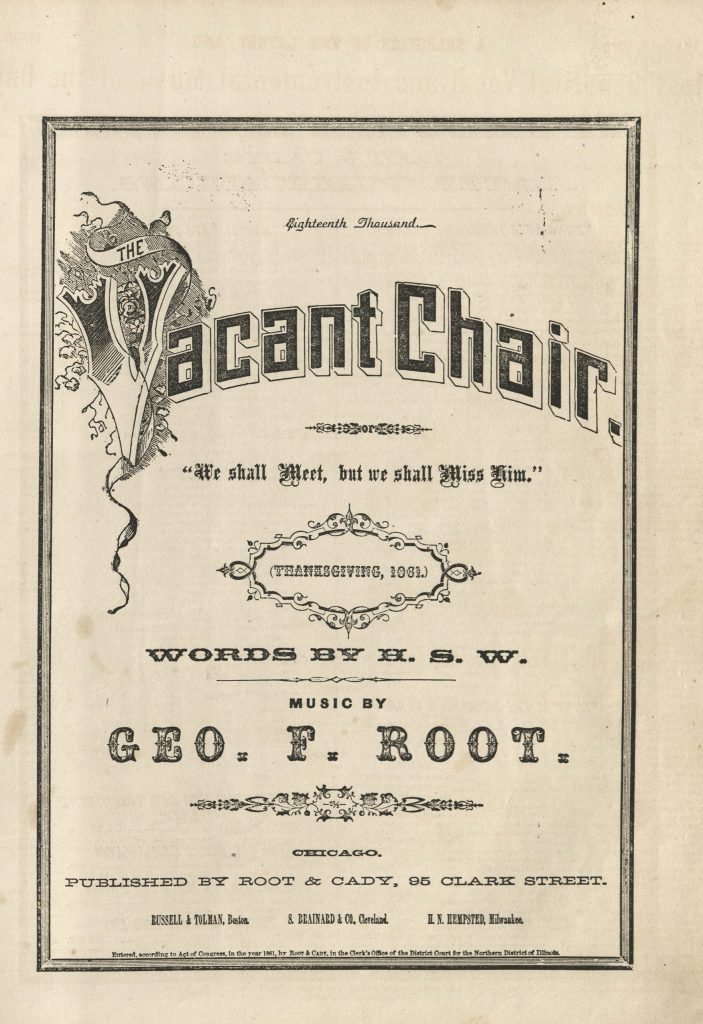

The Vacant Chair: Thanksgiving 1861

November 20th, 2018The Carl N. and Dorothy H. Shull Collection of Hymnals and Music Books, housed in Kenneth Spencer Research Library, includes bound volumes of sheet music. One of those songs is “The Vacant Chair,” with lyrics written by poet Henry Stevenson Washburn (H.S.W.), and set to music by George F. Root.

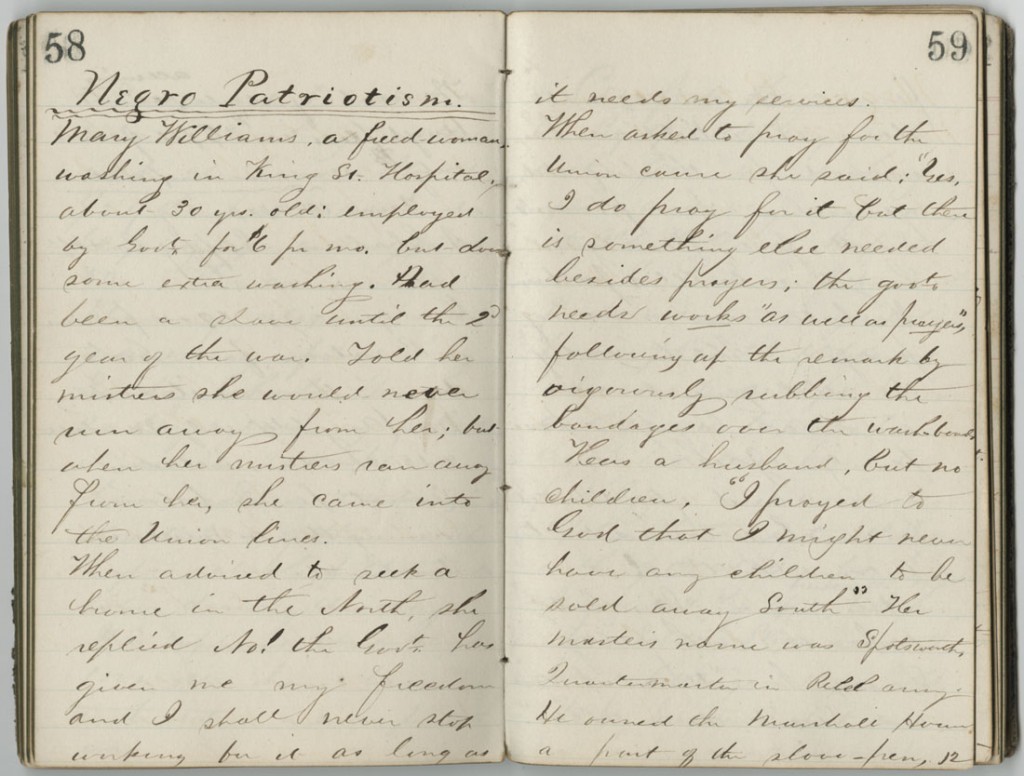

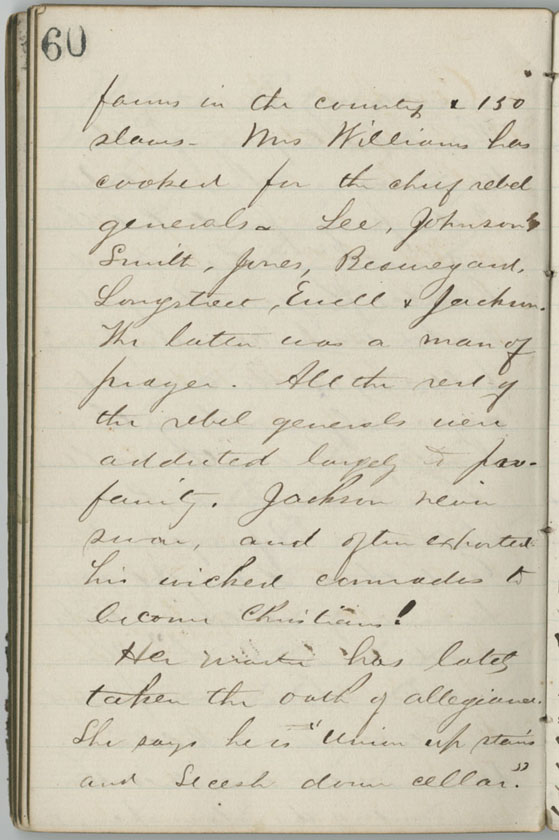

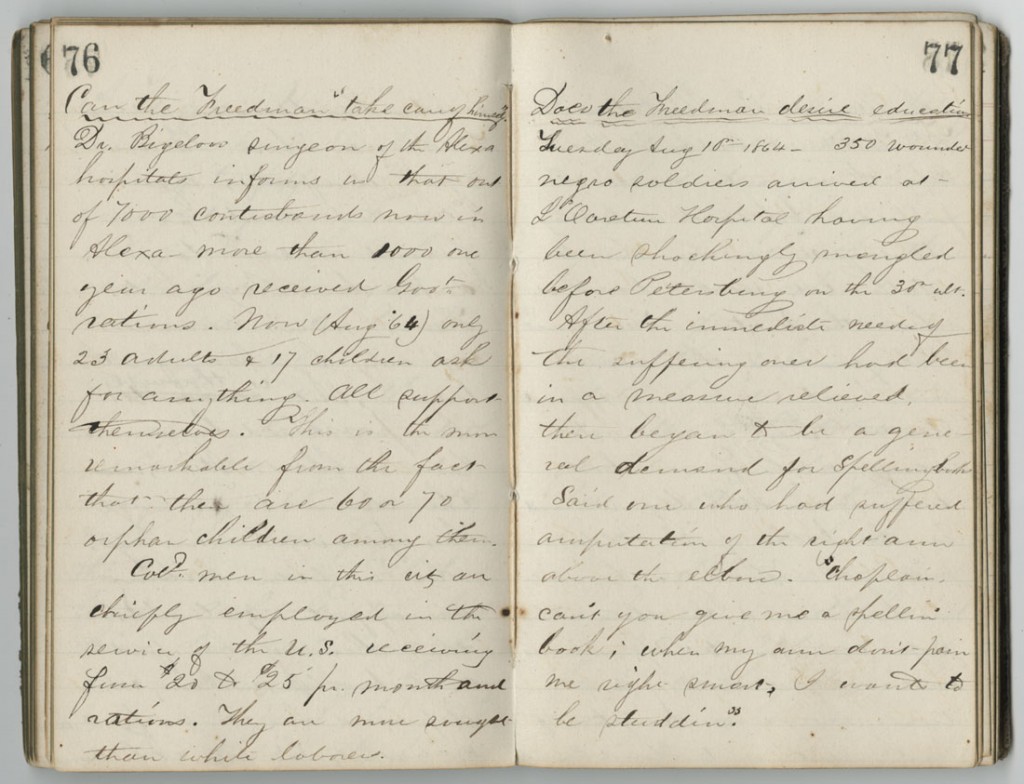

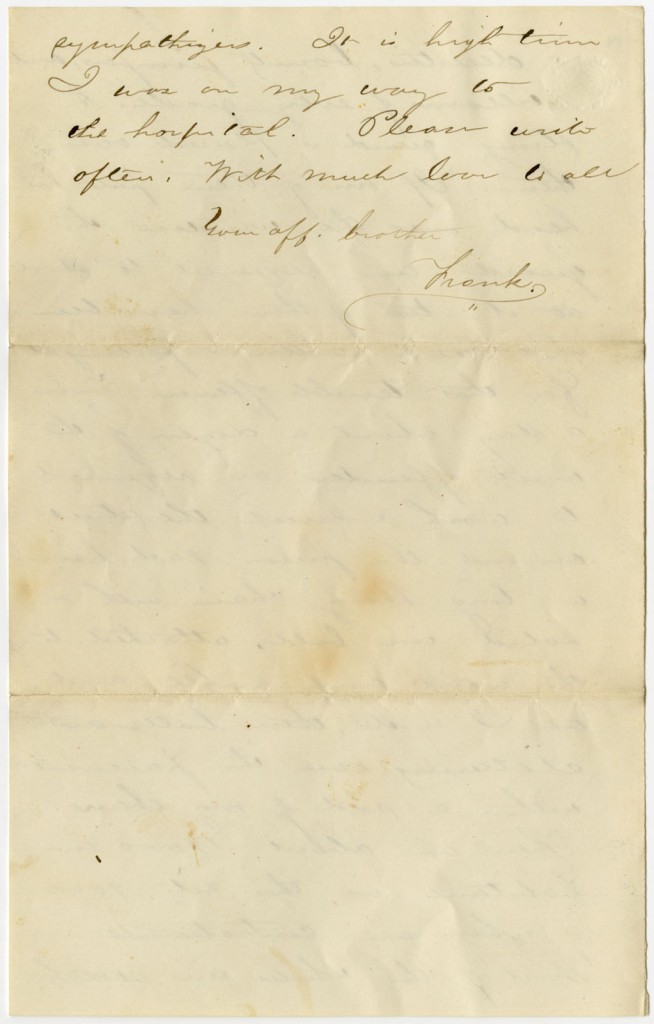

Root, Geo. F. and H.S.W. “The Vacant Chair, or, We Shall Meet, but We Shall Miss Him: (Thanksgiving, 1861).”

Chicago: Root & Cady, 1861. KSRL call number: Shull Score E45, item 14

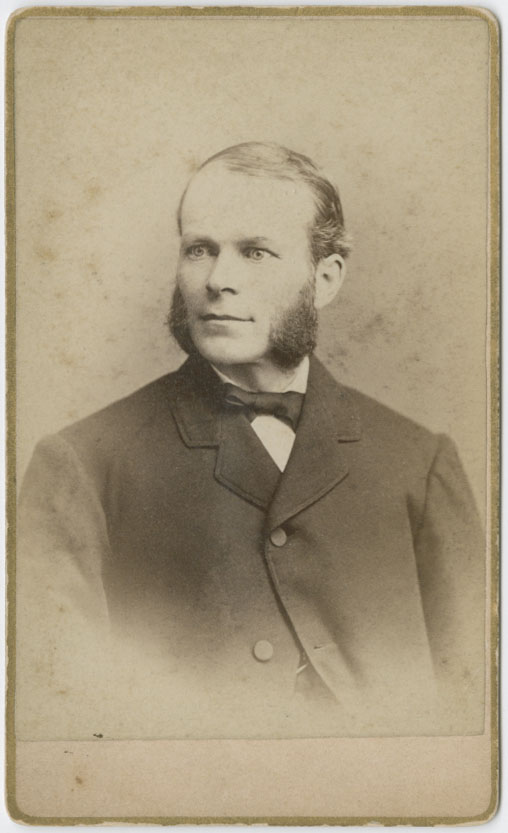

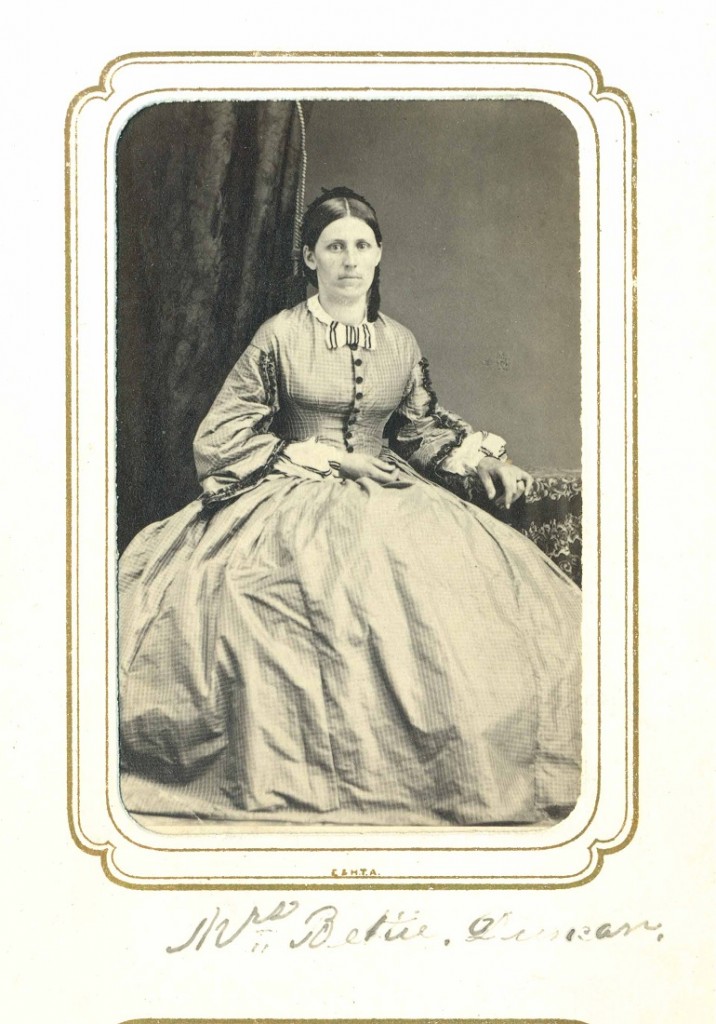

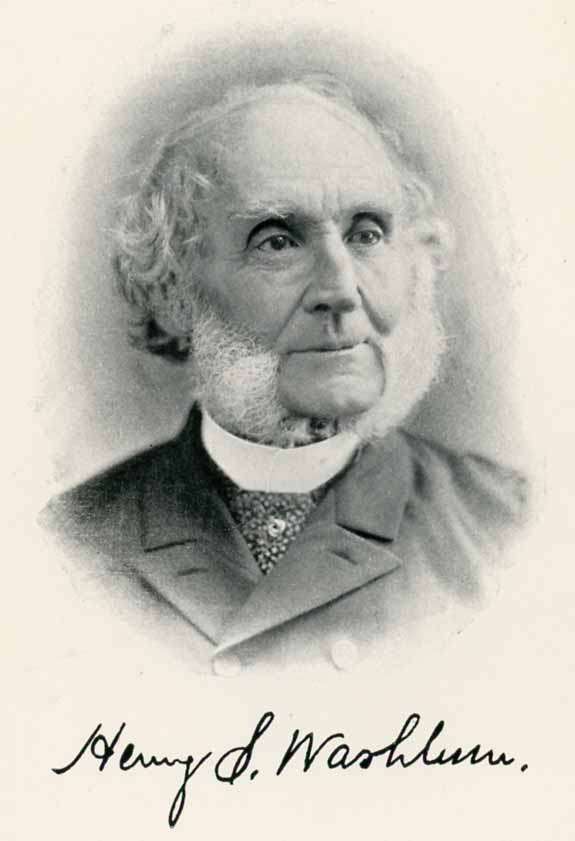

Henry Stevenson Washburn was born on June 10, 1813. He spent his childhood in Kingston, Massachusetts. Throughout his career, he was in manufacturing, was president of Union Mutual Life Insurance Company, and served as both a state representative and state senator. Best remembered for his poetry, he published a book of his collected works in 1895, at the age of 82.

Washburn, Henry S. The Vacant Chair and Other Poems.

New York: Silver, Burdett and Company, 1895, frontispiece portrait detail.

Image from copy obtained via InterLibrary Loan.

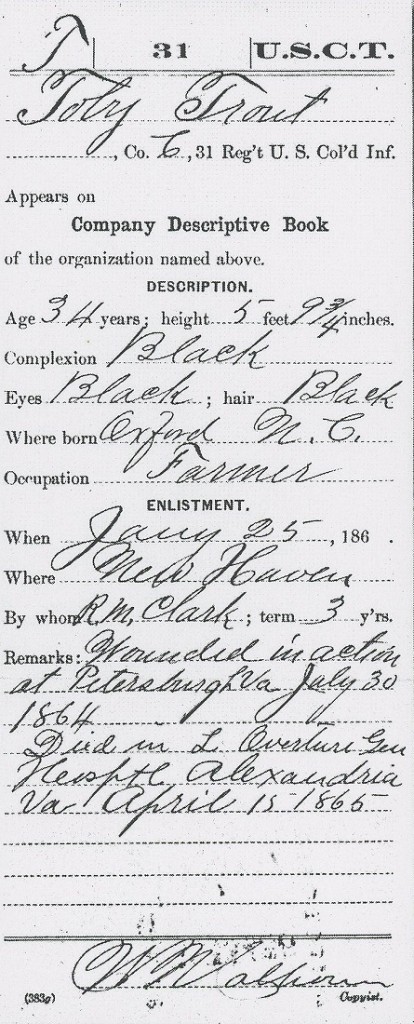

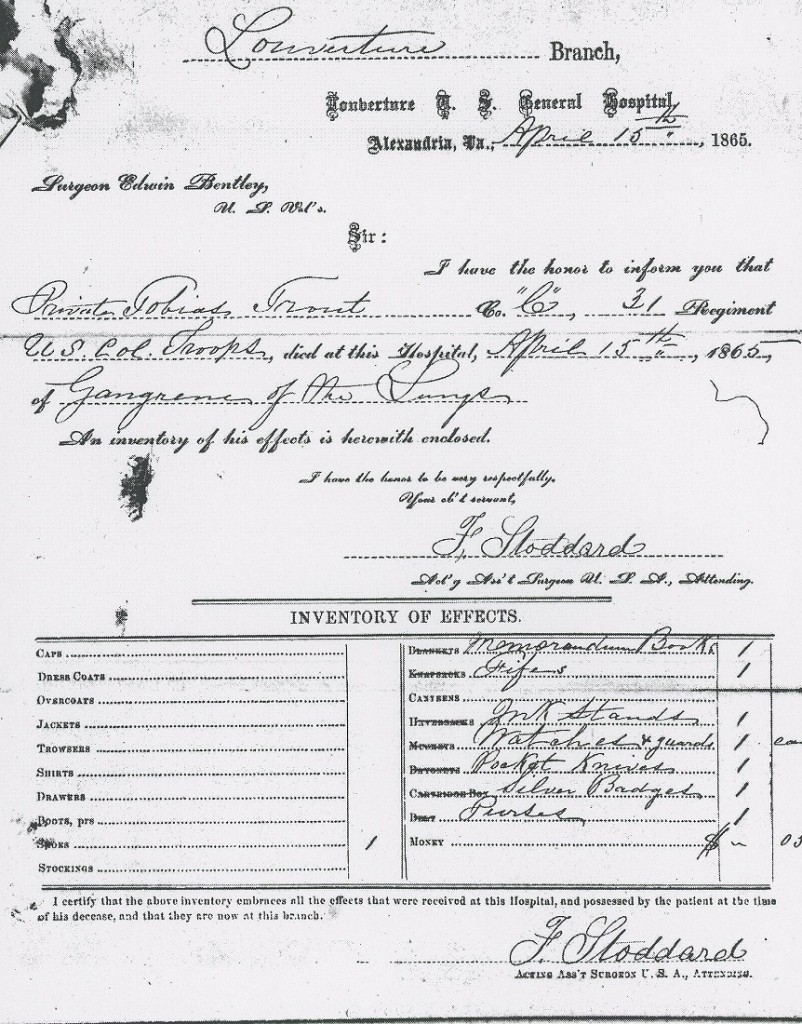

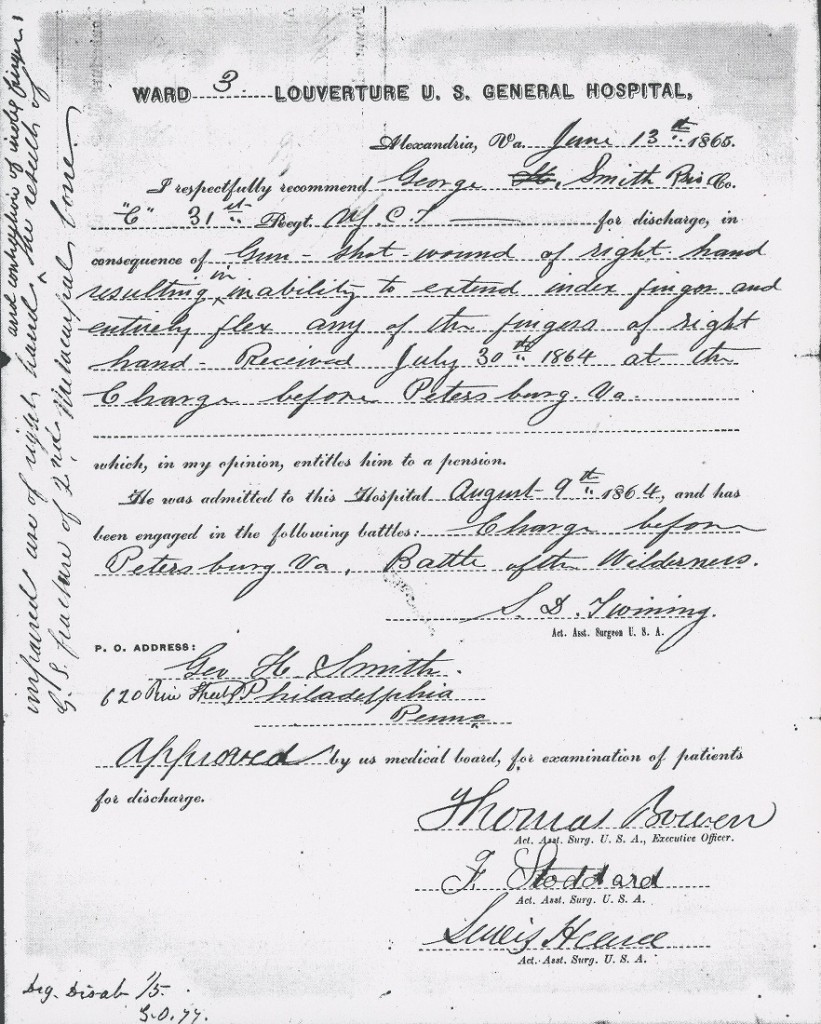

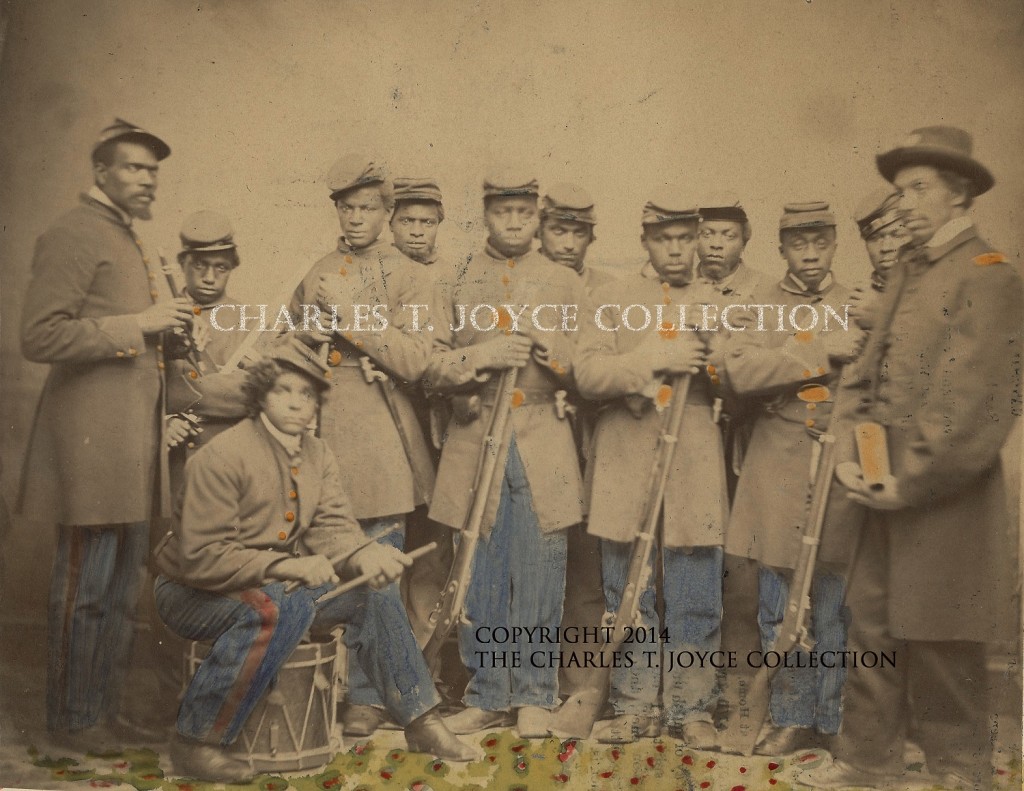

Washburn wrote “The Vacant Chair” in 1861 during the first year of the American Civil War, to memorialize the death of John William Grout, known as Willie, an eighteen-year-old lieutenant in the Union Army from Massachusetts. In his book, The Vacant Chair and Other Poems, Washburn tells the story of how Grout lost his life, selflessly helping his men retreat across the Potomac river under heavy enemy fire at the battle of Ball’s Bluff, Virginia, on October 21st in that first year of war. Mortally wounded, his body, and those of the men who fell with him, floated down river. He was not found until November 5th, identified by his clothing and the letters in his pockets. He was returned to his family, and was buried on November 12th, shortly before the nation, and Willie’s own family, observed Thanksgiving on the 28th. The song became popular throughout the remainder of the war, as many families would experience a “vacant chair.”

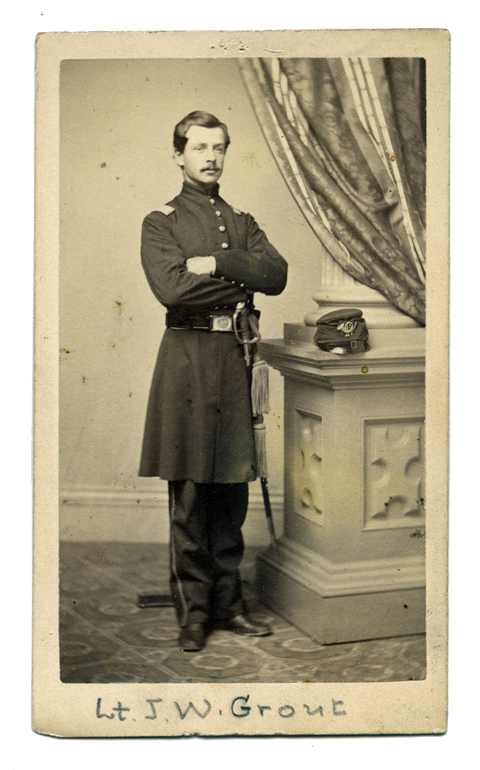

John William “Willie” Grout, 1843-1861, 15th Massachusetts Regiment, Albumen carte-de-visite

by C.R.B. Claflin, Worcester, August 1861. American Antiquarian Society.

Image included in Almanac: American Antiquarian Society Newsletter. No. 81 (March 2011), p. 6.

Recording artist, Kathy Mattea, recorded her version of “The Vacant Chair,” and it is available for listening on You Tube.

The Vacant Chair

We shall meet, but we shall miss him, there will be one vacant chair;

We shall linger to caress him when we breathe our evening prayer.

When a year ago we gathered, joy was in his mild blue eye,

But a golden cord is severed, and our hopes in ruin lie.

We shall meet, but we shall miss him, there will be one vacant chair;

We shall linger to caress him when we breathe our evening prayer.

At our fireside, sad and lonely, often will the bosom swell

At remembrance of the story how our noble Willie fell;

How he strove to bear our banner thro’ the thickest of the fight,

And uphold our country’s honor, in the strength of manhood’s might.

We shall meet, but we shall miss him, there will be one vacant chair;

We shall linger to caress him when we breathe our evening prayer.

True they tell us wreaths of glory ever more will deck his brow,

But this soothes the anguish only sweeping o’er our heartstrings now.

Sleep today, o early fallen, in thy green and narrow bed,

Dirges from the pine and cypress mingle with the tears we shed.

We shall meet, but we shall miss him, there will be one vacant chair;

We shall linger to caress him when we breathe our evening prayer.

Kathy Lafferty

Public Services