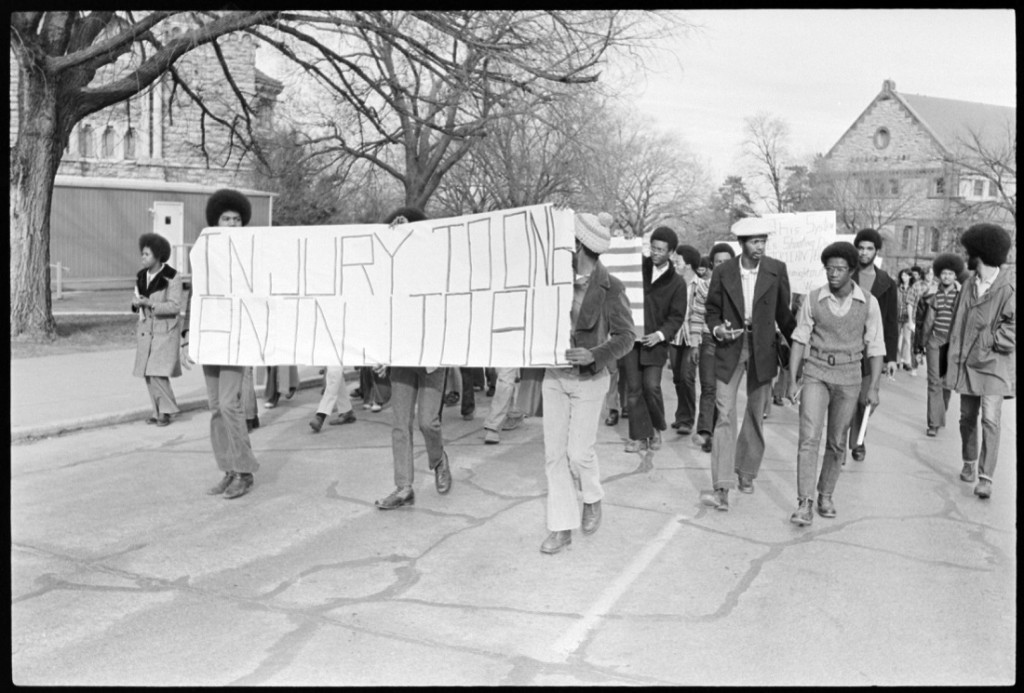

Black Resistance = Kansas History

February 28th, 2023The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) founded the annual February celebration of Black History in 1926 and identified Black Resistance as the theme for 2023.

From Spencer’s African American Experience Collections, I selected the following items to highlight how Black Resistance is an integral part of Kansas history.

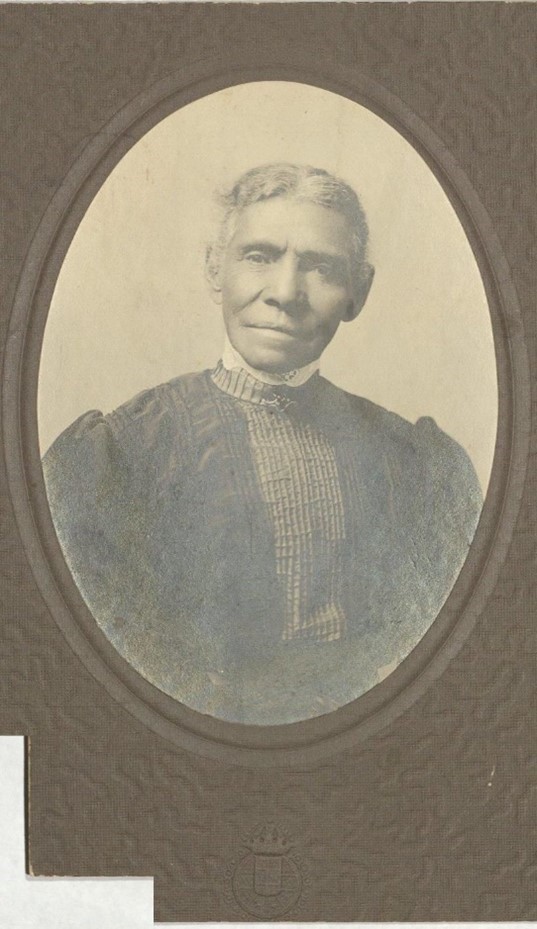

With their baby, William, Mr. David and Mrs. Rebecca (Brooks) Harvey escaped from chattel slavery in Van Buren, Arkansas, by joining a unit of Union soldiers who were going to Kansas. Although the family experienced being separated by accident for two months, they successfully reunited in Lawrence, Kansas, and found employment as tenant farmers on land owned by the state’s Douglas County Sheriff. Within five years, the family saved enough money to buy fifteen acres of land in Douglas County. There they built a home and established their farm. Eventually their farm covered more than two hundred acres.

Kansas is where the family’s four children grew up. William attended business school before spending the remainder of his life working on his family’s farm. Sherman graduated from the University of Kansas in 1889; he then taught in Lawrence public schools and later earned a law degree from KU. Frederick established a medical practice in Kansas City, Kansas, after earning his medical degree from Meharry Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee. And, Edward graduated from KU, worked in Washington, D.C. as a clerk for Congressman J. D. Bowersock, and retired to the family farm while serving as an active leader in Douglas County farm organizations and other civic other civic groups.

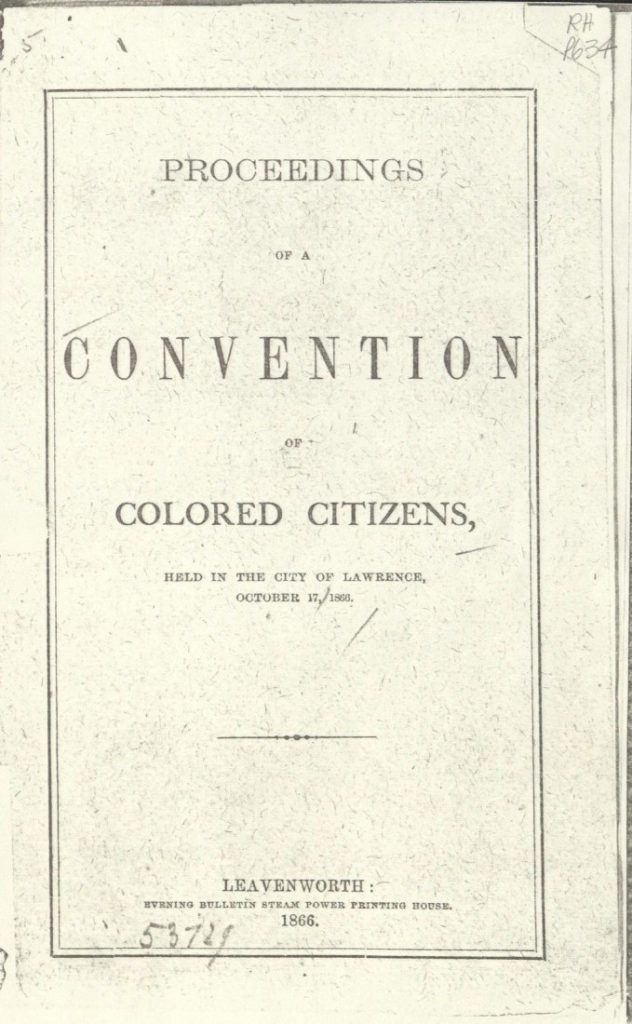

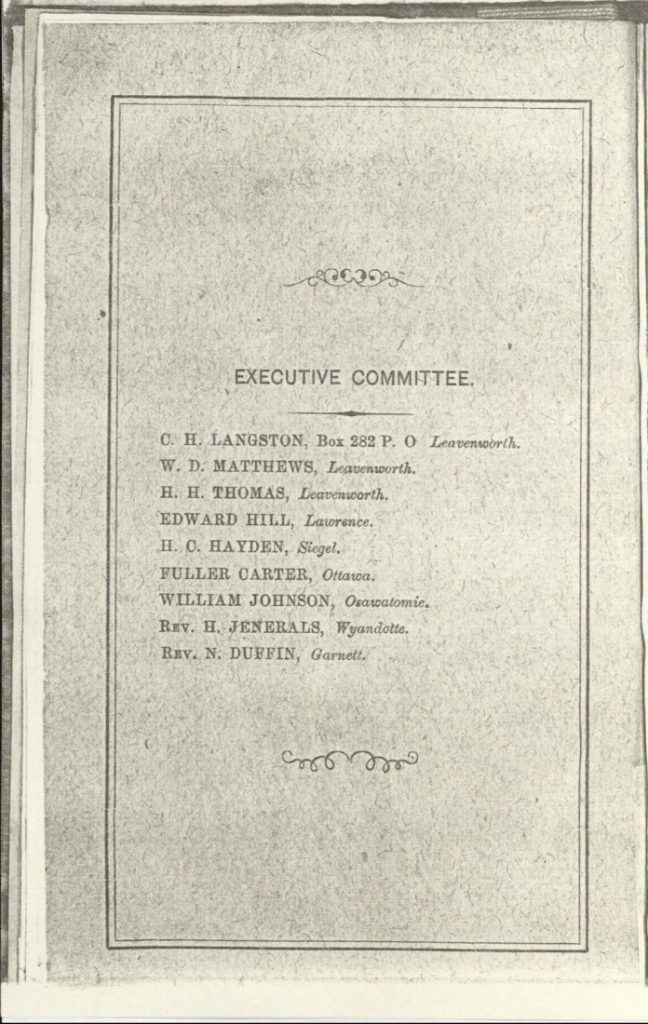

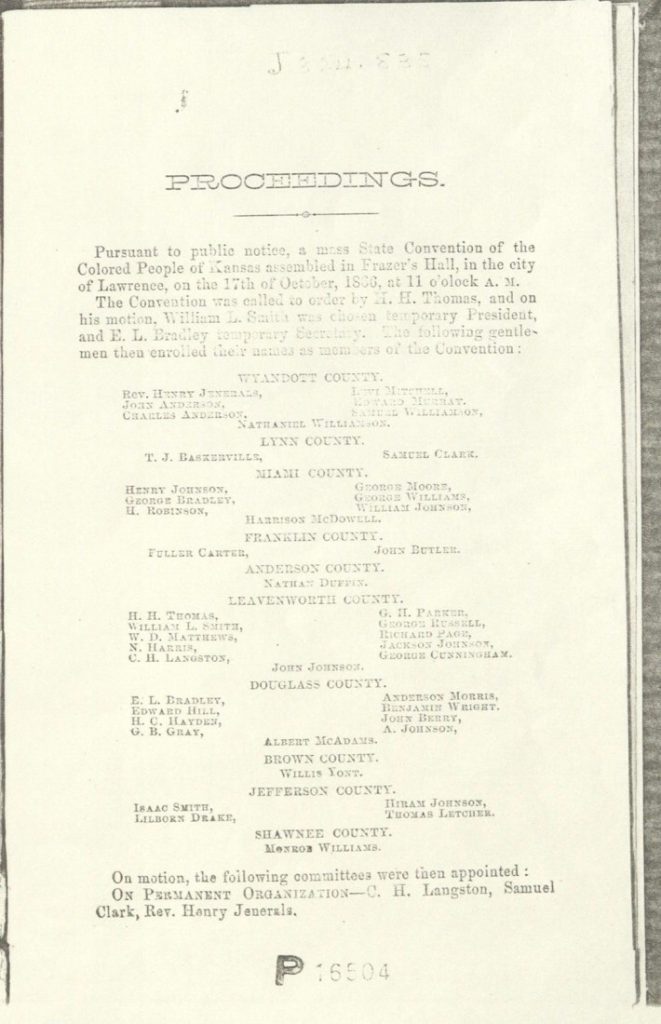

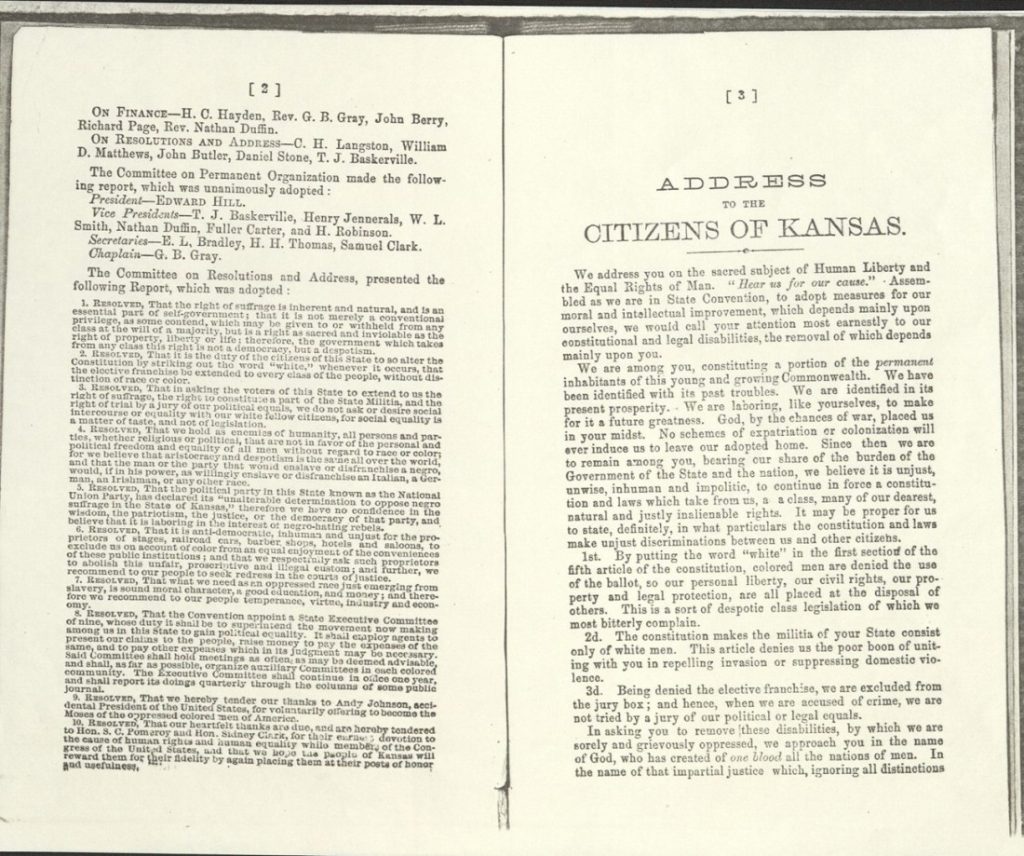

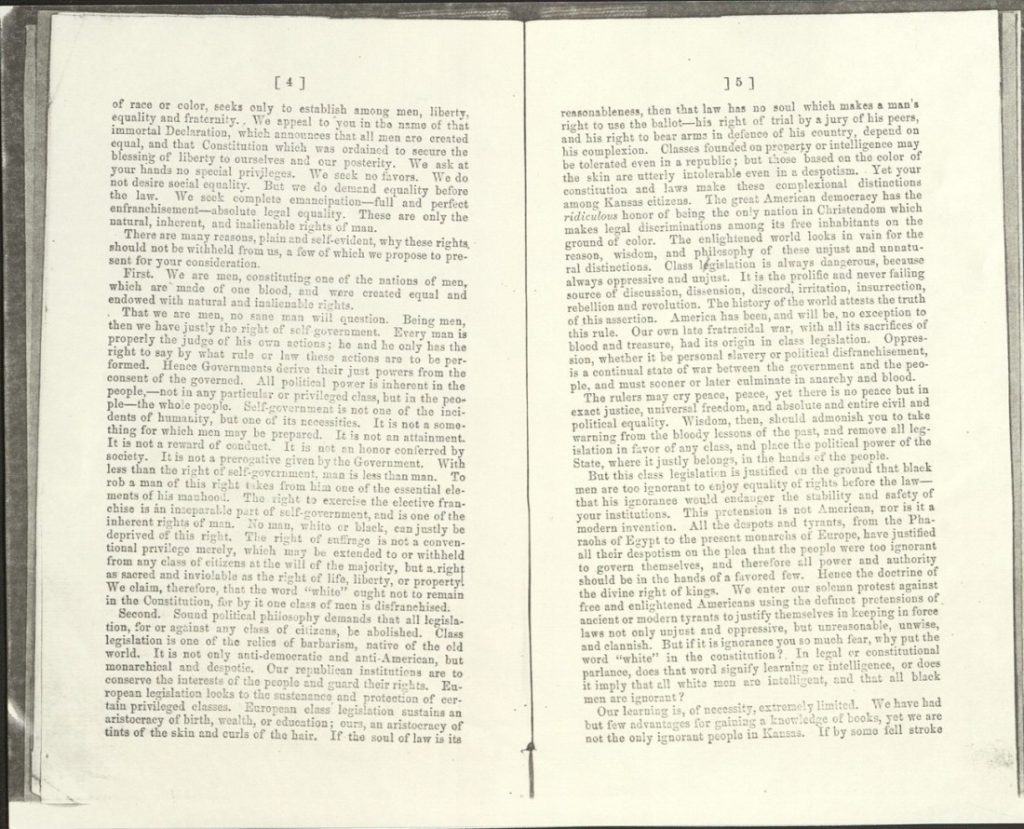

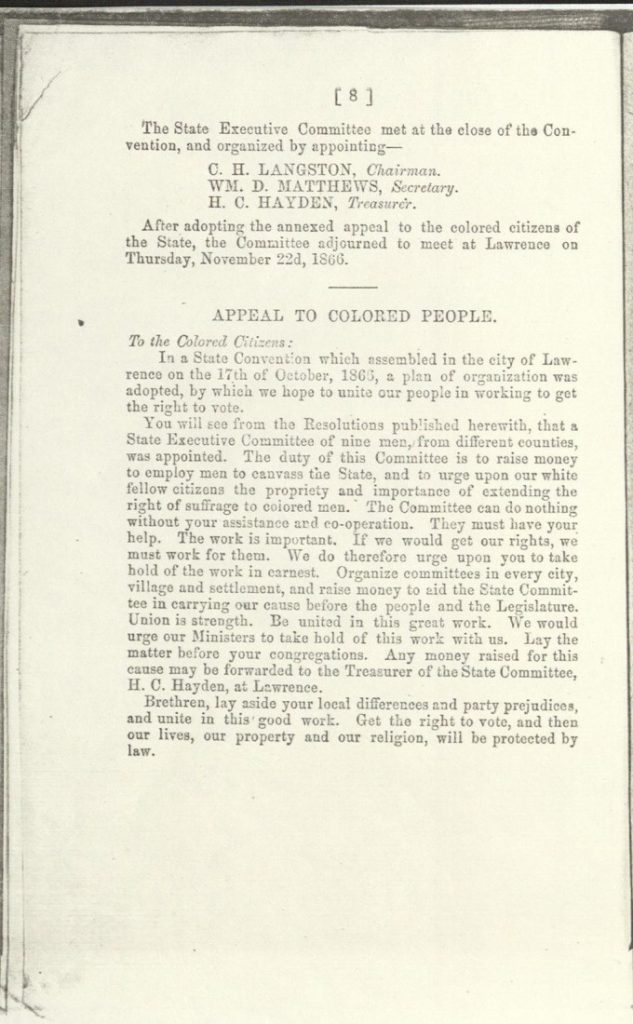

In 1866, the 3rd Annual Convention of Colored Men convened in Lawrence, Kansas, as citizens and taxpayers to advocate for their civil rights, i.e. their right to vote and to serve in the state militia and on juries. The assembled men concluded:

“We are among you. Here we must remain. We must be a constant trouble in the State until it extends to us equal and exact justice.”

Unwilling to be denied better economic and political opportunities, African Americans like the Saddler family shown below migrated from Kentucky, Tennessee, and throughout the nation to Nicodemus in Graham County, Kansas, the nation’s first African American town west of the Mississippi River.

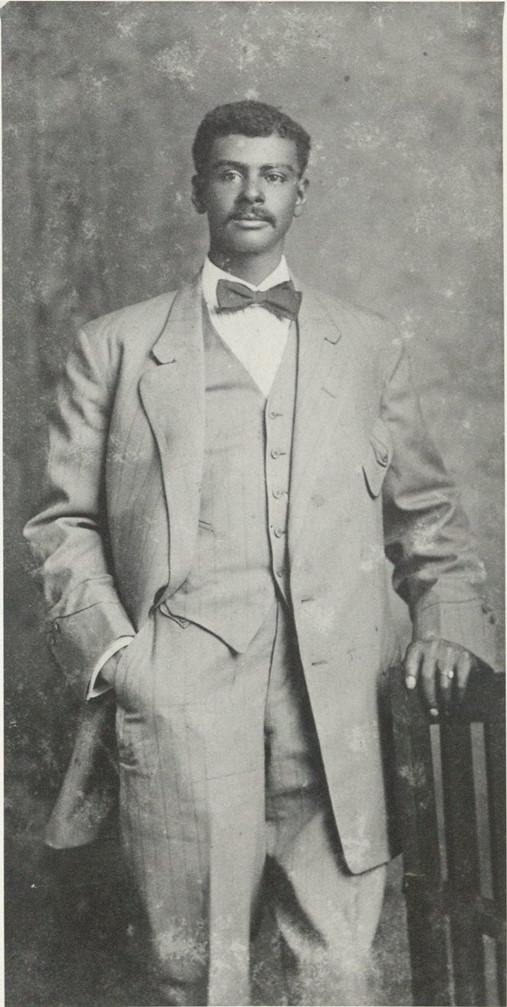

George Williams – the son of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Williams, a prominent farm family in Pratt County, Kansas – filed a racial discrimination lawsuit against the railroad after he was denied access to a train after presenting his ticket to the conductor. Agreeing with a lower court’s findings, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled in 1913 that the train conductor’s action was due to an honest misunderstanding, not racial discrimination. See Williams v. Chicago, R.I. & P. RY. Co. ET AL., 90 Kan. 478, 1913.

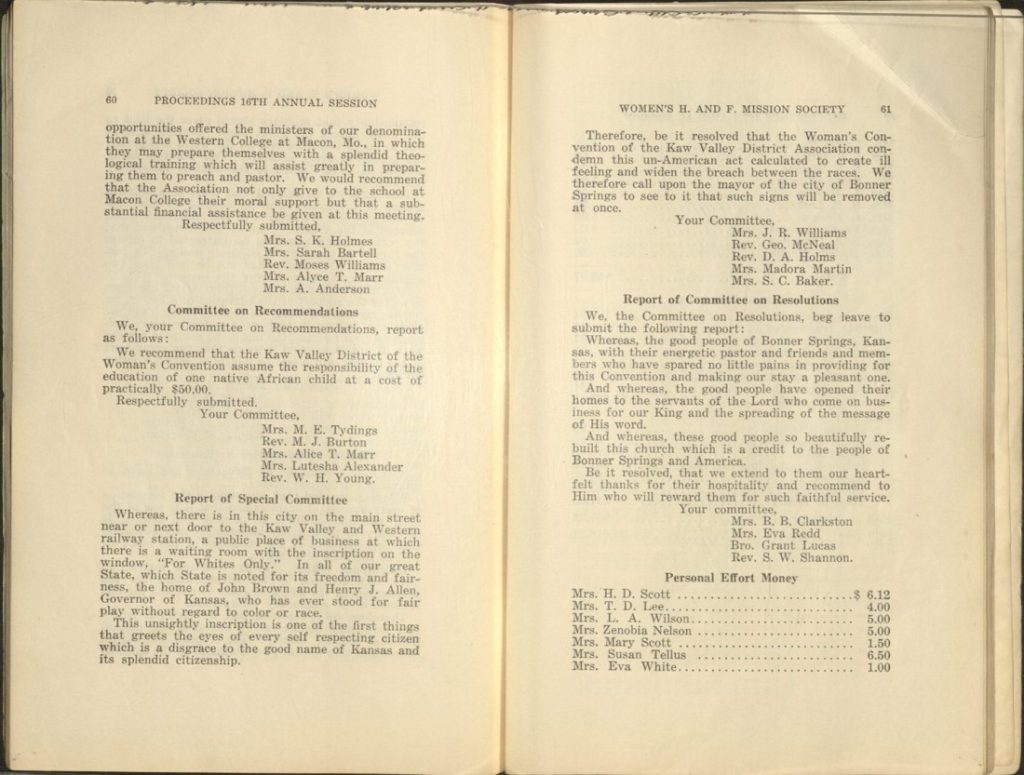

At the 1920 Kaw Valley Convention of the African American Baptist Church in Bonner Springs, Kansas, the Women’s Home and Foreign Mission Society delivered a written protest against a highly visible “For Whites Only” sign displayed in “a public place of business”:

“This unsightly inscription is one of the first things that greets the eyes of every self respecting citizen which is a disgrace to the good name of Kansas and its splendid citizenship.”

Deborah Dandridge

Field Archivist/Curator, African American Experience Collections

Kansas Collection